What I find helpful in John E. Sarno's "The Divided Mind"

Sarno - Tension Myositis Syndrome -Wiki

Forum - Search Forum - Search Forum for "toxic shame"

Abstract

Sarno has experimentally proven that

- we have stored in our brains information which

- we try to understand, meaning to deal predictably with by constructing models: "This is how my friend is, how he thinks, feels." "This is how I need to function at work." "This is New York's Fifth Avenue." (Oliver Sacks "In the River of Consciousness"),

- we find out inconsistencies within our models ("unexpected events") or between our models and (what we perceive as) reality. Then we continuously try to fix these by modifying our models (re-entrant signaling in Edelman's Theory of Neuronal Group Selection, TNGS),

- we become ill (or extremely unhappy) when we cannot repair these inconsistencies,

- we get rid of this illness (unhappiness) by understanding which or our models of reality are causing the painful inconsistencies and by accepting this as universal and a normal component of everyday life.

Sarno analyzes the mind similarly as Oliver Sacks does. Here are details:

Footnote 73 of Oliver Sacks, "Awakenings"

"If we accept Hester's word in the matter (and if we do not listen to our patients we will never learn anything), we are compelled to make a novel hypothesis (or several such) about the perception of time and the nature of 'moments'.

The simplest of these, I think, is to take 'moments' as ontological events (i.e. as our> 'world-moments') and assume that we 'take in' several at a time (as a moving whale continually swallows a swarm of shrimps), or that we keep a small hoard of them 'in stock' at any given time, and in either case 'feed them' into some internal projector, where they become activated and 'real', one at a time in their proper sequence. Normally, this proceeds correctly and easily; but in certain conditions, it would seem, our ontological moments may be fed to us in the wrong order, so that moments which are chronologically 'past' or 'future' get ectopically displaced, and presented to us as utterly convincing (but inappropriate) 'nows'. Somewhat allied hypotheses (of defective or mistaken 'time-labeling' in the nervous system) have been presented by Efron with regard to the commoner but still uncanny experiences of déja vu, jamais vu, presque vu, etc. These are not associated with kinematic vision, but are apt to occur in states of intense and unusual nervous excitements (as in the singular cases of Martha N. and Gertie C.). All these states of anachronism, in company with other time-strangenesses described in this book, indicate how vast is the gulf between abstract and actual, chronological and ontological, in our conceptions and perceptions of time."

Perceptions and models

"Mechanisms of visual consciousness, Crick and Koch feel, are an ideal starting point, because they are the most amenable to investigation at present, and can serve as a model for investigating and understanding higher and higher forms of consciousness." (Oliver Sacks, "In the River of Consciousness").

We experience the world around us by interpreting what we see, hear and feel on the basis of past experience. Put in other words: we filter what enters our senses, the product is our perception.

Our filter works this way: Does the input fit to what we have known up to now?

- If it does, we readily accept the new information,

- if it does not,

- we perceive only as much as we manage to reconcile or to make consistent with our past experience or

- we either feel the inconsistency as a welcome new aspect or we suffer.

Let me illustrate that with an obvious exampe, your visit in Rumpshagen:

I first saw you outside of the house, was happy to get to know you. All of us were strangers, so I used the filter "stranger". When I saw Adèle rushing after Ellis, I loved to put her in my category "caring and considerate". So my impression of her became: she is a "stranger" and "caring and delightfully considerate".

The important thing is: Adèle hasn't changed a bit. Only my perception of her has.

And so it went with all of us. Finally each of us had his/her own mind image "Adèle", "Claire", "Marianne", "Ben", "Ellis", "Jochen". Everyone of us had models of the others, and we became close friends.

I didn't grasp you completely, of course, so I completed my model of you before, in and after the Rollberg Cinema. Again I changed my model-Ben, and you couldn't do anything about it.

Here enters Sarno

If I'll find something out about you that bothers me, I will ignore it so as to keep up the treasured friendship with you. Only if ignoring becomes very painful will I try to mention my problems to you, hoping that I might have misinterpreted your actions or even that you might change becoming more similar to my model-Ben. If you can't do the latter, there is no way you can help me except carefully explain how you are. If I'm still painfully upset, I can't expect more help from you, because it's not you but me who is wrong. But from my perspective things look different, and that's perfectly normal (says Sarno), and so are my problems with that part within you. Once I have accepted that normality, my pain will disappear. That's what Sarno has experienced many, many times. To support this process, he offers some help, and the way he presents his help is redundant to make it easier for us to understand him. I excerpted the sentences that did the trick with me below.

A special treat

Among Sarno's extra recipes is this one: When under some painful stress like the one described above imagine an extremely pleasant situation totally unrelated to the stress at hand. Since reading Sarno's book I love to try this method out e.g. on toxic shame (one of my major problems) - with considerable success. The article I found useful is

Linda Graham, "The Power of Mindful Empathy To Heal Toxic Shame", MFT 2010

The following typical excerpts of "The Divided Mind" helped me understand how this structure acts upon me.

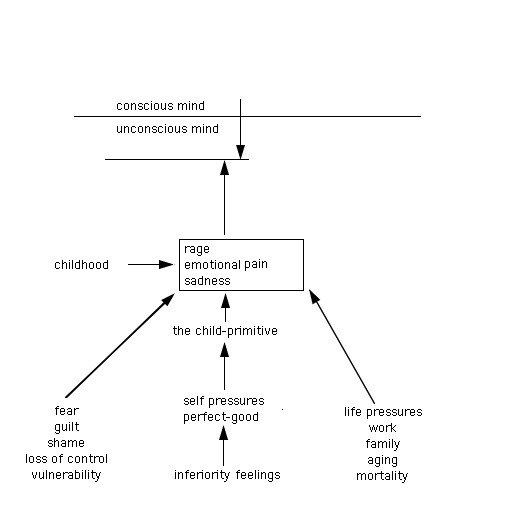

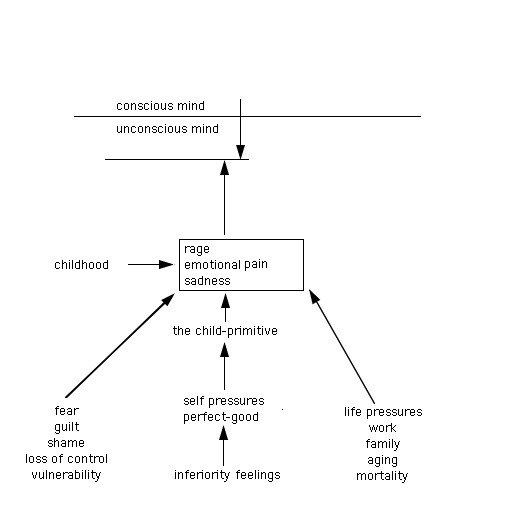

Figure 2 of Sarno's "The Divided Mind"

The division of our mind into two parts, the conscious and the unconscious, is a useful and mostly sufficient simplification of the continuum in our mind between the conscious and the unconscious: we store our experience in a database. The neuronal database is Darwinian, meaning: the more often we recall an information the more available it is to us.

The Child-Primitive

The anatomical persistence of the "old brain" described by Freud and all the behavioral characteristics that are, so to speak, contained in it, is of immens importance not only socially, politically and medically but psychologically as well. It is the part of the brain whose inclinations are in direct conflict with the more responsible, intelligent, moral propensities of the "new brain". The child-primitive is totally narcissitic, irresponsible, and dependent. It harbors the seeds of violence, lust, and obscene behavior and reacts to the pressures of the responsible mind with anger. It cannot stand the pressures to be good, or perfect, or to take care of others, no matter how emotionally close those other might be. A perfect exampe is a young couple with a new baby who happens to be very difficult, crying much of the time. Consciously, the parents are exhausted and worried; unconsciously, they are furious at the baby.

... Anger in the child accumulates and it is permanent because there is no sense of time in the unconscious.

... For many years we were aware of a consistent connection between the perfectionist tendency and the development of Tension Myositis Syndrome (TMS). Though some of our patients denied being perfectionist, they admitted to being hardworking, conscientious, responsible, driven, success-oriented, perpetual seekers of new challenges, sensitive to criticism and their own severest critics. But it was a long time before I realized that the drive to be good could be equally enraging to the child-primitive. It is yet another pressure. Though both the perfect and the good tendencies are present in most patients I see, the good is often the predominant one. These people are aware that they have a great need to be liked and to find themselves looking for approval in everything they do and going out of their way to be helpful, often at the expense of their own comfort and convenience. If you speak to someone who is an inveterate caretaker, helper, do-gooder, you are impressed by the power of the compulsion that drives them. Typically, they avoid confrontation.

... My experience in treating cases of TMS strongly suggests that psychosomatic symptoms are meant to distract, and to protect the conscious mind from dangerous emotions, and we conclude that the need for new symptoms is to guarantee that the protective mission will continue.

... Mr. G, a 40 year old married skilled worker with a daughter had suffered incapacitating back pain for 3 years. He described himself as trying to be a model husband and father, as well as a model son to his aging mother. His father had died when he was 16, and he had to go to work to help support his mother and a younger brother, and abandon his college plans. Later, he married. He got along passably with his wife, though they occasionally engaged in shouting matches when she did not accede to some of his wishes.

In the course of psychotherapy, Mr. G came to realize that he was unconsciously furious at his entire family - his wife, his daughter, his mother and his brother. He resented having had to work so hard to support them, and the fact that they had ruined his chance to go to college. He became aware that in addition to the sadness he felt at his father's death, he felt intense anger at having been abandoned by his father and left with such a burden of responsibility.

The existence of these unconscious feelings were difficult for Mr. G. to accept, but as he managed to do so, his pain receded and he found that he was not as prone to manifest conscious anger at what were clearly irrelevant, nonthreatening targets. Displaced anger, consciously experienced, is common when there is significant unconscious rage. It is a safe substitute for expressing the forbidden rage inside. This is undoubtedly the mechanism behind phenomena like road rage.

... There is an awareness today of the fact that people who are conscientious, hardworking, very responsible, often perfectionist seem prone to develop TMS. Years later it was recognized that the "goodist" tendency was recognized as equally important.

... Helen's psyche, in a desperate attempt to prevent the explosion of those feelings into consciousness, was making the pain worse and worse. And then the psyche lost. Helen began to cry as she never cried before, she raged, she wanted to die. The poison poured out of her and, as it did, virtually all the pain disappeared.

Daily Study Program

- Set aside time every day, possibly 15 minutes in the morning and 30 minutes in the evening, to review the material suggested below.

- Unconscious painful and threatening feelings are what necessitates the pain. They are inside you, you don't feel them.

- Make a list of all the things that may be contributing to those feelings.

- Write an essay, the longer the better, about each item on your list. This will force you to focus in depth on the emotional things of importance in your life. There are a number of possible sources of those feelings:

- Anger, hurt, emotional pain, and sadness generated in childhood will stay with you all your life because there is no such thing as time in the unconscious. Feelings experienced in the unconscious at any time in a person's life, including childhood, are permanent. Physical, sexual, or emotional abuse will cause large amounts of pain and sadness. But not receiving adequate emotional support, enough warmth and love will also result in anger, sorrow, and pain, maybe never felt as a child, but always there in the unconscious. Such things as excessive discipline or unreasonable expectation will also leave emotional marks. Anything that prevents a child from being a child falls into this category and should be put on your list.

- In most people with TMS, certain personality traaits make the greatest contribution to the internal emotional pain and anger. Put these at the head of your lst. If you expect a great deal of yourself, if you drive yourself to be perfect, to achieve, to succeed, if you are your own severest critic, if you are very conscientious, these are likely to make you very angry inside. Sensitivity to criticism and deep-down feelings of inferiority are common and also contribute to inner anger. In fact, feelings of inferiority may be the major reason we strive to be perfect and good. If you have a strong need to please people, to want them to like you, or if you tend to be very helpful to everyone and anyone, if you are the caretaker type and are always worrying about your family, friends, and relatives, these drives will also make you furious inside, because that's the way the mind works. The child in our unconscious doesn't care about anyone but itself and gets angry at the pressures to be perfect and good.

- Just as the inner mind reacts against being perfect or good, it also resents any kind of life pressure. So you should put on your list anything in your life that represents pressure or responsiblity, like your job, your spouse, your parents, if they are living, and of course any big problems that are going on in your life.

- A subtle but important source of inner anger in some people is the fact that they are getting old and also that they are mortal. This is more common than you would think. Consciously we rationalize, unconsciously we are enraged. Close personal relationships, no matter how good they are, are often the source of unconscious anger, because it's very hard to be consciously angry at a person, a spouse or a child.

- Add to your list those situations in which you become consciously angry (or annoyed) but cannot express it, whatever the reason may be. That suppressed anger is internalized and becomes part of the reservoir of rage that brings on TMS. The angers we talked about above are repressed - you don't feel them, you don't know they are there.

Version: 31.7.2017

Address of this page

Home

Jochen Gruber