acamedia.info - Politics --> Germany's Deficit of Accountability ...

Germany's Deficit of Accountability

Continuing into Iraq's Reconstruction Period

Güter

mit doppeltem Verwendungszweck: Das Defizit an deutscher Verantwortlichkeit

nun auch beim Wiederaufbau des Irak

Some Info Material Compiled by

Joachim

Gruber

CONTENTS

Summary

Humanitarian

Misery in Iraq and German Accountability

I. Problem of Dual-Use Items

Summary

I. 1 In Detail

Old

system (before May 2002)

New system

I.

2 UN Documentation

I.

3 Iraq: The Day After

I.4

The Tradition of the Marshall Plan

II. Germany's Accountability

II.

1 Compliance of German/Austrian Firms with the Spirit of Nonproliferation

II. 2 Deficits in German Peace Research

III. Transatlantic Partnership: Excerpts from a Proposal to Promote a Partnership for Democracy and Human Development

IV. Appendix

IV.1

The Present: Assistance to Iraq After the 2003 War - Inadequate Grants

from Germany

IV.

2 The Past: Search for the Cause of the Humanitarian Misery

IV.

2. a Iraq Didn't Agree to Targeted Sanctions

IV. 2.

b Saddam's Obstruction

Summary

Humanitarian Misery in Iraq and

German Accountability

-

The Office of the Humanitarian Coordinator in Iraq (UNOHCI) is an integral part of the Office of the Iraq Programme (OIP ). In April and October 1999 Hans Graf von Sponeck, then (second) United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq, informed the public about the humanitarian situation in Iraq. In particular, he pointed out that there are mostly multiple reasons (rather than just one) for e.g. delays in making food/medicine available in Iraq. His stance on the oil-for-food program was focused on the humanitarian effects of the sanctions, and -seeing no other way to improve the disastrous situation- he advocates a lifting of the type of sanctions in effect during his term as coodinator, which has been done in May 2002. Security Council Resolutions - Oil-for-Food Programme

-

As described below, after sanctions had been considerably relaxed, more than half of Iraq imports came from Germany. Our (German) country has a particularly bad record when it comes to proliferation of technology for weapons of mass destruction.

-

Since apparently the majority of firms trading with Iraq are from Germany, we should make every effort at avoiding the sale of dual-use items to Iraq when we cannot exclude misuse on the Iraqi side. Instead of meeting the demands of a cynical government, our industry could offer technology that would prepare Iraq for a possibly important role in a post fossile fuel future.

"... recent history has demonstrated that post-conflict peace-building can be exceptionally complex. In Iraq, where U.S. efforts will involve uncertainty, trial and error and uneven progress, U.S success will depend on our determination to sustain a long-term and substantial commitment of American resources (an estimated minimum of $ 20 billion per year for several years) and personnel, to ensure the active involvement of others in post-conflict reconstruction, and to promote participation by the people of Iraq in a process that validates their expectations about political reconciliation and a more hopeful and democratic future (Testimony of Eric P. Schwartz before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, published by the Council on Foreign Relations, Iraq, March 11, 2003, see also report referred to in Testimony: Iraq: The Day After, Report of an Independent Task Force on Post-Conflict Iraq, Sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations, Thomas R. Pickering and James R. Schlesinger, Co-Chairs Eric P. Schwartz, Project Director). |

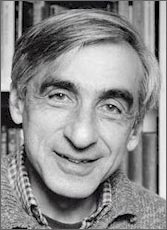

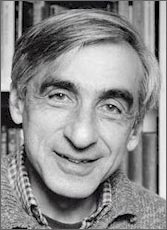

Hans von Sponeck, a German,

was appointed the UN Humanitarian

Coordinator for Iraq in 1998.

A year and a half later he resigned,

claiming that 150 Iraqi children

die each day as a result of US sanctions.

"I felt I was being misused

for a UN policy that was punitive,

that tried to punish a people

for not having got rid

of their leader," he says.

(Radio

Netherland,

"Weapons

of mass illusion", 2002)

|

INTRODUCTION

Multilateralism, Accountability and Universal Principles

... multilateralism requires help from outside the US. It would be easier to make our case if it were clear that there were other agents in international society. capable of acting independently and, if necessary, forcefully, and ready to answer for what they do, in places like Bosnia, or Rwanda, or Iraq. When we campaign against a second Gulf War, we should also be campaigning for that kind of multilateral responsibility. And this means that we have demands to make not only on Bush and Co. but also on the leaders of France and Germany, Russia and China, who, although they have recently been supporting continued and expanded inspections, have also been ready, at different times in the past, to appease Saddam. If this preventable war is fought, all of them will share responsibility with the US. When the war is over, they should all be held to account."

(Michael Walzer, The Right Way, New York Revew of Books, March 13, 2003). |

|

Michael

Walzer

Michael Walzer has written about

a wide variety

of topics in political theory and

moral philosophy:

political obligation, just and unjust

war,

nationalism and ethnicity,

economic justice and the welfare

state.

He has played a part in the revival

of

a practical, issue focused ethics

and in the development of a pluralist

approach

to political and moral life.

(M.W.,Schol

of Social Science,

Insitute

for Advanced Study, Princeton, USA)

|

"... America's thinking about its engagement with the world is being bedeviled by the insistent asking of the wrong question, which is: how can we close the rift with Europe caused by the Bush administration's "unilateralism", which betokens wariness about international institutions and international law? The right question is: do we really want to close this rift?

It reflects fundamental differences between American and European understandings of constitutional democracy. So argues Jed Rubenfeld in a mind-opening essay forthcoming in the Wilson Quarterly.

Rubenfeld, a Yale Law School professor, wonders why America - which after 1945 was the principal progenitor of today's system of international organizations and law, including the United Nations - has come to be regarded as hostile to that project. His answer is that Cold-War unity between America and Europe disguised what is now patent: diametrically opposed American and European views of the objectives of international law and organizations. ...

...between America and the European democracies there are irreconcilable differences concerning constitutional democracy. ...

-

American constitutionalism does indeed check democracy, but remains accountable to democracy, to elected representatives and legislatures that can amend it, and to presidents and senators who nominate and confirm the judges who construe it.

-

European constitutionalism speaks with a Paris accent, using the language of universal truths defined by intellectual elites and presented to publics which are expected to be deferential.

Europe likes to think of itself as ancient Athens, supplying wisdom to muscular America, the modern Sparta. But it is more illuminating to think of today's tensions as arising from differences between two 18th-century cities, Philadelphia and Paris. "

(from G.E. Will, Paris vs, Philadelphia, Newsweek, Oct. 13, 2003) |

|

Jed

Rubenfeld

|

Anne-Marie SLAUGHTER: "... the people who had

horrors of democracy, as you put it, were our own Founding Fathers

who were very concerned about democracy per se, and spent

most of their time putting in checks and balances to guarantee

liberal democracy, which of course ensures protection of minority

rights, exactly because we have principles that cannot be trumped.

To that extent, the EU and we both agree that you need liberal

democracy. And the notion that the EU is built--is designed to

avoid fascism--the EU is designed to avoid war between France and

Germany in part. That war had happened plenty of times before you

had fascism and Nazism. And it was an economic means to peace. It

was not designed as a check on democracy, and to the extent there

are checks, it's--as I said, let's start with Madison.

But then let's stick to some facts of the current EU, because I

think this is really quite important.

- The first point is that the entire EU bureaucracy is the size of the government of a good-sized American city. That's the commission.

- The real power in Brussels lies with the Council of Ministers, [which is made up of] all their national ministers. And indeed the real struggle in Europe is persistently between those who want a more federal vision and those who insist on keeping the power among the nation-states. You will have noticed, those of you from the financial community, that the European Central Bank does not seem to be able to keep Germany within the guidelines. Well, that's remarkable for this anti-democratic powerful institution.

- The European Court of Justice, unlike our own Supreme Court, has 12-year terms--not for life. Why do they have 12-year terms? So that judges who get too activist can be dismissed and then new ones appointed. And that's exactly what happened when Germany and England decided the European Court of Justice was a little too activist for its taste, unlike our own system where judicial activism is up to the Supreme Court and they are there for life.

... on universal principles, we are the ones that preach

universal principles, founded in the Declaration of Independence.

We preach them worldwide. We insist that countries all over adopt

those principles as part of the liberal democratic heritage. And we

may allow them in the room when we draw up their constitutions, but

the constitutions are still recognizing the same bill of rights we

have.

Finally, and back to international law, the great irony of this is that the European tradition of international law is completely grounded in state consent.

For those of you who are not lawyers, this is what is called the positivist tradition. It says no natural law, no law founded in a higher reason, [but instead] law grounded on the consent of states.

It's American international lawyers who insist on universal human rights, led by Jed's dean, Harold Koh at Yale. It is American international lawyers who insist that international law is shot through with politics, and in the end we should simply recognize what is right for the protection of human dignity, and to advance that.

So there are critiques to be made here. But there's no

connection to the EU, to European countries themselves, or to

international law.

... I strongly suspect that the reason no Kosovars were on the commission is because Kosovars want a separate country, and we do not want them to have a separate country, and that that was a starting point that could not have gotten over. ..."

(from: "Is International Law a Threat to Democracy?", Speakers: Anne-Marie Slaughter (dean, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University), Jed Rubenfeld (Robert R. Slaughter professor of law, Yale Law School), Moderator: Fareed Zakaria (editor, Newsweek International), transcript of a debate, Council on Foreign Relations New York, New York, February 27, 2004)

|

|

Anne-Marie Slaughter

|

I.

Problem of Dual-Use Items

Summary

In the old

sanctions system, many supplies, desperately needed to repair the infrastructure,

are banned or restricted as "dual-use" items, capable of use as military

supplies. This includes chlorine, needed for water purification.

http://www.irak.be/ned/kalender/CAMPAIGNERS%20Guide.htm,

http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/iraq_wmd/Iraq_Oct_2002.htm

The general direction of the sanctions

was changed

-

from allowing only food/medicine

-

to principally allowing all goods

(Sources:

1. Fact

Sheet on the "Goods Review List" for Iraq, 14 May 2002, US

Department of State, International Information Program.

2. Revised

U.N. Goods Review List Strengthens Scrutiny over Exports to Iraq, 14

January 2003, US Department

of State, International Information Program.

I.

1 In Detail

-

Old system

(before May 2002): The Iraq Sanction Committee, comprised of all 15

members of the Council, reviewed almost all of Iraq's proposed purchases

-with foodstuffs and certain medical, health and agricultural materials

exempt from review. Any member of the committee could approve, hold or

block a proposed contract. In reviewing proposed purchases, members referred

to established international control lists of items related to nuclear,

chemical and biological weapons, ballistic missile programs and conventional

weapons. Over time Iraq was permitted to export increasing quantities of

oil, and the types of goods it could purchase expanded. From 1999 on, Iraq's

oil exports have been unlimited.

-

New system

(SRC 1409

- 986 Application Processing Chart, local

link): All contracts for export of goods to Iraq under the Oil for

Food program are presumed approved unless found to contain item(s) on the

"Goods Review List" (GRL). A Goods

Review List was established, i.e. a list of items controlled for export

to Iraq under U.N. Resolution 1409 adopted by the U.N. Security Council

in May 2002. Contracts containing items on the list are reviewed by the

U.N. Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as well as the Sanctions Committee

organized pursuant to Resolution 661. It is not a denial list.

Firms make it -sometimes apparently

on purpose- hard for these new targeted export controls to work.

I.

2 UN Documentation

UN documentation seems intransparent.

It appears time consuming to extract from UN documents on the internet

information such as presented

by the US State Department, i.e. the development over time of how much

was allowed for import (import ceiling) vs. how much was actually bought

by Iraq from proceeds of oil sales under the OFF program, deposited on

UN escrow account.

Data I found on the OFF program

Excerpts from these documents

-

Agreement: Although established in April 1995, the implementation of the programme started only in December 1996, after the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the United Nations and the Government of Iraq on 20 May 1996 (S/1996/356). The first Iraqi oil under the Oil-for-Food Programme was exported in December 1996 and the first shipments of food arrived in March 1997.

Funding: The programme is funded exclusively with proceeds from Iraqi oil exports, authorised by the Security Council. In the initial stages of the programme, Iraq was permitted to sell $2 billion worth of oil every six months, with two-thirds of that amount to be used to meet Iraq’s humanitarian needs. In 1998, the limit on the level of Iraqi oil exports under the programme was raised to $5.26 billion every six months, again with two-thirds of the oil proceeds earmarked to meet the humanitarian needs of the Iraqi people. In December 1999, the ceiling on Iraqi oil exports under the programme was removed by the Security Council

-

Dividing the Money: With the adoption of Security Council resolution 1330 (2000) on 5 December 2000, around 72 per cent of the oil revenue funds the humanitarian programme in Iraq (59 per cent for the centre and south and 13 per cent for the three northern governorates); 25 percent goes to the Compensation Commission in Geneva, while 2.2 per cent covers the United Nations costs for administering the programme and 0.8 per cent for the administration of the UN Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC). Previously, 66 per cent was being allocated to the humanitarian programme (53 per cent for the centre and south and 13 per cent for the three northern governorates), with the Compensation Commission receiving 30 per cent of the revenue. Funds from the two humanitarian accounts finance the purchase of oil industry parts and equipment. The Government of Iraq is responsible for the purchase and distribution of supplies in the 15 governorates in the centre and south. The United Nations implements the programme in the three northern governorates of Dahuk, Sulaymaniyah and Erbil on behalf of the Government of Iraq.

-

Delivery: To date, some $26 billion worth of humanitarian supplies and equipment have been delivered to Iraq under the Oil-for-Food Programme, including $1.6 billion worth of oil industry spare parts and equipment. An additional $10.9 billion worth of supplies are currently in the production and delivery pipeline.

-

Oil-for-Food Plus: The Programme, as outlined in the latest report of the Secretary-General, has been expanded beyond its initial emphasis on food and medicines. Its scope and level of funding includes infrastructure rehabilitation and covers 24 sectors: food, food-handling, health, nutrition, electricity, agriculture and irrigation, education, transport and telecommunications, water and sanitation, housing, settlement rehabilitation (internally displaced persons - IDPs), mine action, special allocation for especially vulnerable groups, and oil industry spare parts and equipment. The Government of Iraq introduced the following 10 new sectors in June 2002: construction, industry, labour and social affairs, Board of Youth and Sports, information, culture, religious affairs, justice, finance, and Central Bank of Iraq."

I. 3 Iraq: The Day After "Iraq: The Day After" is a Report of an Independent Task Force on Post-Conflict Iraq, Sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations, Thomas R. Pickering and James R. Schlesinger, Co-Chairs, Eric P. Schwartz, Project Director, March 2003.

Testimony of Eric P. Schwartz Before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Tuesday, March 10, 2003. These five questions are addressed:

-

What is the extent of our long-term

political commitment to Iraq? What are we prepared to spend, and when will

the administration describe this in detail to the American people?

-

What specific actions will the U.S.

military take to protect Iraqi civilians in the context and the aftermath

of conflict?

-

What action is the administration taking to ensure that international organizations and other governments will contribute meaningfully to the post-conflict transition effort?

-

What actions are being taken to ensure the Iraqi character of the political transition process?

As a government, are we well organized to meet this challenge?

|

|

Eric Schwartz, Senior Fellow, Peace and Conflict,

US Council on Foreign Relations

Former national security official in Clinton administration and director of a US Council on Foreign Relations-sponsored independent task force on Post-Conflict Iraq.

|

The US government will contribute to the post-conflict transition process in Iraq via the US Agency for International Development (USAID) - much as it has been doing during the war. The Schwartz-Report will be one of the documents on which this work will be based.

I.4

The Tradition of the Marshall Plan

USAID was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy in the tradition of the Marshall Plan. This aid for Japan and Europe rested on the practical interest of many Americans in the furthering of democracy, on "how the taste for physical gratification is united in Ameica to love of freedom and attention to public affairs" (Alexis de Tocqueville, 1834). This is behind the many organizations in which Americans meet and -mostly after the day's work- develop new ways of life.

Such an organization ist the Religious Society of Friends ("Quaker"). One of the most known "Friends" was William Penn. The "Friends" are a religious community with headquarters in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

"Its work is based on the belief in the worth of every person, and faith in the power of love to overcome violence and injustice. Founded in 1917 to provide conscientious objectors with an opportunity to aid civilian victims during World War I, today the AFSC has programs that focus on issues related to economic justice, peace-building and demilitarization, social justice, and youth, in the United States, and in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East (e.g. Iraq) , and at the United Nations (Geneva and New York)."

(About AFSC).

|

|

William

Penn (1644-1718)

"No pain, no palm;

no thorns, no throne;

no gall, no glory;

no cross, no crown."

- from No Cross, No Crown

|

| Arthur R.G. Solmssen, a lawyer and novelist from Philadelphia, has written a novel about this: Following his time driving French ambulances at the front in 1917, Peter Ellis, a young Quaker, spends some years in the turbulent Berlin of the 1920's among two German cultures. His own tradition is the basis for his compassionate forms of friendship and help (Summary, "How can I describe Miss Susan Boatwright?", "Silence

with Voices"). |

|

Arthur R.G. Solmssen: A Princess in Berlin |

II.

Germany's Accountability

II.

1 Compliance of German/Austrian Firms with the Spirit of Nonproliferation

Companies make export controls difficult

-

In August 1984, Germany also

imposed a new regulation requiring the licensing of whole chemical plants

and certain chemical equipment suitable for the production of chemical

weapons agents and precursors. This was especially aimed at the exports

by Karl Kolb to Iraqi chemical weapons facilities in Samarra. Karl Kolb,

however, won a court case in which it contested blocking of its shipments.

On February 15, 1989, the German Cabinet introduced a requirement for an export license for plants suitable for the production of biological agents and tightened the definition for the requirement for an export license for chemical plants.

-

[In 1990,] Daimler-Benz manufactured 26 Mercedes-Benz tractors and 20 trailers for export to TECO for Project 144 Al Walid Group (codename for one of Iraq's SCUD missile enhancement programs), found by U.N. inspectors to be capable of use as mobile Al Walid launching pads for the Al Hussein missile; general contractor in supplying to SOTI and TECO Project 144 an unspecified number of "non-civilian version" trucks and "military type" equipment, including the 26 Mercedes tractor trucks; the 20 trailers were low-loading, specially equipped flat-bed tractor trailers produced by the German subsidiary of French firm Marrel; four tractors were fitted with infra-red protected covers; all trailers were fitted with camouflaged lights and support legs; German offices raided; investigation found that no license was required; investigation dropped based on possible non-military uses (Source: Iraq Watch. Iraq's Suppliers, Daimler-Benz).

-

Austrian Benda-Lutz

sells aluminium powder flakes (size 25 - 35 mm,

aluminium content 95.3 percent by weight) meeting an Iraqi order dated

18. November 2002. These flakes can be used as constituent chemicals for missile propellants according to the Missile Treaty Control Regime (MTCR) Annex Handbook. The Goods Review List, Missile Section, item 3.3.1, page 35 specifies "Metal fuels in particle sizes less than 500 x 10 -6 m (500 mm), whether spherical, atomized, spheroidal, flaked or ground, consisting of 97 percent by weight or more of any of the following: zirconium, beryllium, boron, magnesium, and alloys of these." http://www.welt.de/data/2003/02/24/45054.html?s=1

II.2 Deficits in German Peace Research

German Peace research seems to limit

its work on the Iraq problem to

-

general analyses of basic character,

carefully avoiding to address the role of Germany,

-

repeating and citing results achieved in US research institutions.

In view of the impact Germany's contribution to world politics has today, this seems to reflect a lack of accountability on the side of research that is supposed to advise the public and government.

Example: Although widely discussed in the German public, the issue of foreign aid to a post-Saddam Iraq seems to lie beyond the scope of German research. Contrary to that, the US Council on Foreign Relations independent Task Force on post-conflict Iraq has addressed 5 questions in its study Iraq: The Day After

(more) Examples of unconcerned German Peace Research Institutes

Analyses of German research are heavily tainted by ideology and do not develop possible options of action. Example: IFSH-Report "Krieg mit dem Irak", 12. February 2003:

-

The list of facts is incomplete,

-

the analyses are not based on original

research performed by IFSH or other German institutions.

-

no course of action for Germany is offered.

In particular:

-

Section "Foreign Policy" mentions Iraqi trade of weapons and industrial goods with France, but neglects to mention trade with Germany, although more than half of Iraq's imports have come from Germany (CNS, Report München, Khidhir Hamza, Bagdad International Fair 2001, Iraq Watch, J. Gruber).

-

Section "Has Iraq Met its Disarmament Obligations?" report about the period 1991 until today, criticises the military intervention of the US and Great Britain, but not the loopholes in German export control and the resulting serious violations by German industry of nonproliferation treaties relating to the technology of weapons of mass destruction (District Court of Augsburg, Germany, Iraq

Watch).

-

Section "Does Iraq Threaten the World with Weapons of Mass Destruction?" points out the success of UNSCOM and UNMOVIC, but not the influence of US and Great Britain's military pressure nor that Germany has not submitted any accountable propositions for its own course of action (e.g. the future extent and type of trade with Iraq).

-

Section "What Comes After the War?" doubts the preparedness of the US to cover the costs of Iraq's reconstruction, but misses discussing the future role of Germany (and other European countries) in a peaceful, future-oriented development of Iraq.

Examples of US research institutes (more)

The consequences of this apparently deficient research are detrimental, e.g. - Germany's Foreign Minister Fischer hat to rely on data and analyses from US research institutions when explaining Germany's position in the UN Security Council.

-

German research has not published on the internet any information on possible proliferation of weapons of mass destruction technology or know-how or breach of export laws by German industry. (see also "Export controls in the crea of chemical and biological weapons", The Federal Foreign Office, July 2000)

III. Transatlantic Partnership: A Proposal

Excerpts from Urban Ahlin, (Member of the Swedish Parliament)

Mensur Akgün (Turkish Economic and Social Science Studies Foundation)

Gustavo de Aristegui (Member of the Spanish Parliament), Ronald D. Asmus (The German Marshall Fund of the United States), Daniel Byman, (Georgetown University) et al, "Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership Istanbul Paper #1", German Marshall Fund of the United States(gmfus) and the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (T.E.S.S.F.), 25-27 June 2004 (download document from Centre For European Reform (CER) website)

In the fall of 2003 the German Marshall Fund of the United States formed a working group to debate what a transatlantic strategy toward the broader Middle East might look like. We did so as part of our commitment to fostering greater understanding and common action between the United States and Europe on new, global challenges facing both sides of the Atlantic in the 21st century. ...

Retooling the Transatlantic Relationship to Promote a Partnership for Democracy and Human Development

To prepare to meet this longterm challenge, the United States and Europe must focus on reorganizing themselves in three key areas.

-

Upgrading Our Knowledge

We need to create a new generation of scholars, diplomats, military officers, and democracy builders who know the region's religions, languages, history, and cultures, and who have the skills to advise our leaders on the best policies and how to pursue them appropriately.

American and European levels of

knowledge and understanding of the broader Middle East have been declining for years. That trend now must be reversed. Just as the West had to create a new generation of experts to better understand Europe and the USSR after 1945, we now need to create a new pool of expertise and talent to better analyze the broader Middle East. What can be done? While we do not face the kind of monolithic bloc or single threat we faced from the USSR during the Cold War, nevertheless, the manner in which the West organized itself then offers lessons for today. In the United States, for example, the federal government provided funds to establish new studies centers at leading American universities to systematically study both Europe and the USSR as well as to teach the language skills needed to understand a part of the world about which we still knew little. Through exchange programs, Americans and Europeans were able to gain firsthand expertise in the countries that were top foreign policy priorities. Regional expertise and strategic studies were brought together to provide an integrated understanding of the region and the key strategic issues governments were grappling with.

In addition, the United States and leading European allies set up special programs to bring young leaders and legislators from both sides of the Atlantic together to foster a common view and approach on the major strategic challenges of the day.

In both the United States and Europe, competence on these issues deemed central to America's or Europe's national security became a prerequisite for a successful career in national security as well as for anyone aspiring to national office. Today we need to think in similarly bold and ambitious terms. We need, first and foremost, to deepen our knowledge of the broader Middle East and of the complex historical and cultural background to the current problems in the region. On both sides of the Atlantic, we need a new generation of experts who combine knowledge of the Middle East, democracy promotion, and strategic studies. Today it is rare to find a program at any leading American or European university that produces this combination of expertise. Neither the department of government at Harvard nor the department of political science at Stanford University has a tenured faculty member specializing in the region. The situation at leading European universities is little different.

In addition, we need to expand contacts with key leaders in the region representing an array of societal actors, including both governments and civil society.

Today many American and European government officials, legislators, diplomats, or military officers have not only a cursory understanding of the region, but also of their counterparts.

A parallel effort is needed to bring American and European leaders together to discuss what a common transatlantic strategy to the region should be.

The same programs and institutions which promoted a common view on how to deal with core European security issues in the past must now be reoriented to face these new issues. Academia and the think tank world will not fill this void unless prompted by government or private foundations on both sides of the Atlantic.

-

Reorganizing Our Structures

A strategy to promote democracy and human development in the broader Middle East will also require us to reorganize our national security and foreign policy establishments to highlight this new priority.

At the moment, the task of democracy promotion is buried down in the second, or even third, tier of our foreign policy bureaucracy. Promoting democracy and political reform is often considered something slightly exotic - a distraction even from the daytoday exigencies, as opposed to a core priority - especially when it comes to the broader Middle East. If this issue is to become a top national priority for decades to come, then it needs to be treated as such in our own policymaking structures. As mentioned earlier, both American and European governments have started reorganizing themselves in response to the new threats we face from the broader Middle East.

-

The creation of the Department of Homeland

Security, for example, is one of the largest governmental reorganizations

in the United States in decades.

-

In Europe, the pace of change has been

slower but is now accelerating as the EU has stepped up its intelligence

and lawenforcement coordination and has also created a new coordinator

for terrorism.

-

Both sides of the Atlantic are debating

potentially far reaching reforms of their intelligence communities and

defense establishments.

Thus far, there has been no equivalent

effort to upgrade the task of democracy promotion and human development

in the broader Middle East to an equivalent national priority. This needs

to change.

-

Doing a better job at penetrating terrorist

cells,

-

stopping the terrorists at our borders,

or

-

having a better capability to defeat

them in those cases where we actually confront them militarily is not enough.

-

We need to be as good at supporting

democratic transitions and/or engaging in nation building as we are at

toppling despotic or tyrannical regimes.

The need for more effective strategies and capabilities in this area has been obvious for some time. In recent years, successful military operations ranging from the Balkans to Iraq have been followed by much weaker efforts at political and economic reconstruction. We urgently need to improve our postconflict reconstruction performance. More important still, we need to improve our ability to affect peaceful democratic change. Acquiring that capability requires a reorganization

of our current national security institutions.

There are different ways in which one can approach this key task. We believe that governments on both sides of the Atlantic should consider separating the task of democracy promotion and human development and elevating it to a senior level where it will enjoy highlevel political support and can command the resources necessary for the task.

-

In the United States this would mean

creating a cabinet level Department for Democracy Promotion and Development.

-

The Europeans for their part should create an equivalent EU Commissioner with the same responsibilities in the new European Commission. When the EU appoints a new Foreign Minister under the new Constitutional treaty, this Commissioner for democracy and human rights should become one of his or her deputies.

The rationale for this step is simple. In the United States,

-

the State Department's mission is diplomacy between states, not helping the transition to democracy or promoting human development.

-

The Pentagon's mission should remain

defense;

-

its assets for regime reconstruction should be moved into this new department, which would also appropriate resources from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other government departments and agencies. This new department must be endowed with prestige, talented people, and, above all, resources. The point of creating these highlevel posts is to give leadership and political accountability to both American and European efforts to promote democratic change.

-

Reforming the Transatlantic Partnership

These changes would also help to build a better foundation for creating a common transatlantic strategy vis a vis the broader Middle East. Despite the breadth and depth of the transatlantic relationship, currently there is no place where the two sides meet on a regular basis to develop and coordinate a common strategy along such lines. While NATO is the strongest institutional link across the Atlantic, it is a military alliance whose focus is too narrow to serve as the forum to coordinate our policies in the areas laid out in this paper. The Alliance can make an important contribution to such a strategy but it will not be

the central player.

On paper, the U.S./EU relationship potentially could become a key forum for both sides of the Atlantic to coordinate polices and build a common approach.

The EU has experience and a number of assets in the area of promoting democracy, even if its track record has, thus far, been often timid and inconsistent. However, it would require a significant overhaul and upgrade of a relationship that neither side has heretofore used as a key venue for issues of such importance. At the same time, such an overhaul is long overdue

-

as the United States looks for

a venue to coordinate strategy on nonmilitary issues and

-

as European nations turn over

responsibility for policy on these issues to Brussels.

The relative weight of the three elements

of the transatlantic relationship - NATO, relations with capitals, and

U.S./EU - is changing. In years to come more transatlantic 'traffic' will

have to go through the EU/U.S. channel, especially when it comes to the

broader Middle East.

In the 1990s, the United States and its European allies took a transatlantic relationship that was forged during the Cold War and designed to contain Soviet power and transformed it into a new partnership focused on consolidating democracy in Central and Eastern Europe, halting ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, and building a new partnership with Russia. Today this relationship and its key institutions must again be overhauled to meet a new set of challenges centered in the broader Middle East. A strengthened U.S./EU relationship and a transformed NATO can become key instruments in developing and pursuing such a strategy - if our leaders today are as creative and bold in adapting them as the founding fathers were in establishing them a half century ago.

Conclusion

Promoting democracy and human development

in the broader Middle East is a historic imperative - for the peoples and

societies of the region as well as for the United States and Europe.

The democratic reform and transformation of this region would be a critical step forward in ensuring a more peaceful and secure world. Assisting this region in meeting the challenges of human development, modernity, and globalization would be a critical step in combating terrorism and in providing an antidote to the radical fundamentalist movements that employ it.

Meeting this challenge is first and foremost a challenge for the peoples and governments of the region itself. But the outside world -and North America and Europe in particular- can and should help. Developments in the region today have a direct impact on our security and wellbeing. The threats emanating from radical terrorist movements constitute one of the greatest dangers to our societies and to world order. Both strategically and morally, our own interests are tied up with this region's future.

That is why we believe that American

and European interests are best served by pooling our political strength

and resources to pursue a common strategy of partnership with the region.

At the moment, there is a danger that Europeans and Americans will pursue competing democratization strategies. Whilst both sides bring different things to the table - and there are real advantages in complementarities - it would be far more effective to pool the best proposals available on both sides of the Atlantic and to coordinate their implementation in a joint endeavor. One of the great historical lessons of the 20th century is that the world is a much safer, more peaceful and democratic place when America and Europe cooperate. That is as true today as it was in the past.

There is perhaps no more fitting task than for the democracies of North America and Europe to come together to help promote democracy and human development in a part of the world where it is most absent and most needed. Our governments have taken the first steps in recognizing the failings of our past policies and in accepting the need to steer a new course vis a vis the region. We welcome these initial steps. At the same time, we believe there is a need for bigger and bolder thinking about the specifics of a future Western strategy. This paper is meant to stimulate discussion on this issue - on both sides of the Atlantic as well as in dialogue with our partners and interlocutors in the region.

We hope it will be received in that

spirit. We look forward to a dialogue on these ideas.

III. APPENDIX

IV.1

The Present: Assistance to Iraq After the 2003 War - Inadequate Grants

from Germany

"This is a moment of historic

opportunity in Iraq, it's something that we need to move on quickly, it's

something that if we don't move on quickly there will be very, very bad

consequences in the future. And we hope that other governments will see

it the same way, that they will make an extra budgetary effort recognizing

the importance of this particular task." (Alan P. Larson, US Under Secretary

of State for Economic, Business and Agricultural Affairs; Preview

of Iraq Donors' Conference in Madrid, October 23-24, 2003, Foreign

Press Center Briefing, Washington, DC, October 22, 2003).

"And by focusing the effort on this

window of opportunity, we could make a huge difference for them [the people

in Iraq], but also for the security of the entire world." (John B. Taylor,

US Under Secretary of Treasury for International Affairs, Preview

of Iraq Donors' Conference in Madrid, October 23-24, 2003, Foreign

Press Center Briefing, Washington, DC, October 22, 2003).

"This has been

a historic occasion for my country, which a little over six months ago

was the black sheep of the international community. When Iraqi delegates

made speeches or asked for support, the conference halls emptied and the

silence was deafening.

"Today I am again proud to be an

Iraqi. My colleagues and I came to Madrid to ask for support in the huge

task ahead of us in reviving our country, and the support has been outstanding.

Iraq has made many new friends. In the last few days I have met with representatives

of dozens of countries who have offered to help us build a secure and stable

future for our country. In years to come the Iraqis will remember who came

forward to help them and to help us in our time of need.

The pledges made today will help

us get back on our feet. Iraq should not need help. As others have said,

we are a rich country made temporarily poor. We are a proud people who

want nothing more than to stand proud again and to reach our huge potential.

We will return to Iraq confident that the reconstruction needs of Iraq

will be met. The pledges made today represent a huge investment by the

international community in Iraq.

A very significant portion of the

overall reconstruction needs are identified by the UN and by the World

Bank in their research report. As this investment starts to pay dividends

in Iraq, we expect to be able to start funding more and more of these needs

through our auditors and once we have fully repaired the criminal damages

done by the former corrupt regime, we look forward to joining future conferences

on the other side of the table as a donor, not a recipient." (Ayad Allawi,

President of the Iraqi Governing Council, Press

Conference following the International Donors Conference for the Reconstruction

of Iraq, Madrid, 24 October 2003)

F

or each announced German Iraq-aid

US$

the US citizen has given already

14 US$ Iraq-aid

(as of April

22 2003).

|

"International sanctions against

the Iraqi regime led to the collapse of the economy, and over half of the

country's population has become totally dependent on food rations distributed

by the government under the UN Oil-for-Food program. Humanitarian agencies

have been trying to prepare for the human cost of conflict for months,

yet difficulties obtaining access for assessment missions and preparedness

activities and lack of funding have hampered and delayed these efforts.

Two million people may become internally displaced, leaving them in search

of food and shelter, adding to the 1 million people who are already without

homes. Refugees--as many as 1.5 million--could flee to neighboring nations.

10 million Iraqis--40% of the population--may need immediate food aid.

5.2 million of those who may need immediate food aid are children younger

than five or women in some stage of childbearing or infant care. The potential

costs of humanitarian assistance for just the first six months are likely

to run as high as $800 million." (American

Council For Voluntary International Action, Emergency

Relief in Iraq, April 2, 2003). |

ReliefWeb is a project of the United

Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

|

Public Donation Information

The most effective way people can

assist relief efforts is by making cash donations to humanitarian organizations

that are conducting relief operations. A list of humanitarian organizations

that are accepting cash donations for their activities in the Gulf can

be found in the "How Can I Help" section at [www.usaid.gov/iraq].

U.S.

Outlines Humanitarian Assistance for Iraq

|

|

Donor and International Organization

Assistance to Iraq

(mostly Governments)

Total Volume as of April 4, 2003:

$1.2

Billion

(was drawn from ReliefWeb

and may be not comprehensive)

click on graphics for legend

Assistance

for Iraq (see also: Relief

Web - Iraq)

Total Volume: $1.2 billion

-

total US State/USAID assistance to Iraq

in FY 2003: $530 million

-

rest of the world (as of April 4, 2003):

$714 million

Total volume as of

April

22, 2003: $25 billion

Total volume = $25 billion, i.e.

-

$1.2 billion as of April 4, 2003

-

plus USA

-

plus $1.3 billion in assistance pledged

by

other donors.

Update summary

as of October 20, 2003

-

> 20 billion from USA

-

>

1.5 billion from Japan

-

0.9 billion from UK

-

0.3 billion from Spain

-

0.1 billion from Germany.

Update summary

as of October 24 and November

6, 2003

-

Total grant volume: $33

billion

-

US: $ 20

billion

-

more than $13 billion from other countries

and international organizations, including

-

Japan: $ 5

billion

-

European Union: $1.44 billion, including:

-

Spain: $300 million

-

Denmark: $27 million +

-

Italy: $235 million

-

Germany: $ 0.1 billion

-

Republic of Korea: $200 million

-

Canada: over $150 million

-

World Bank: between $3 and $5 billion

in loans

-

International Monetary Fund: between

$2.5 and $4.25 billion in loans

Of related interest: the issue of grants

versus loans. |

IV.2

The Past: Search for the Cause of the Humanitarian Misery

The common argument against the

disastrous humanitarian consequences of the sanctions is that Saddam

himself caused the misery.

-

M. Ignatieff, Containment

of Iraq: Status and Challenges, March 2001

-

US

Dept. of State material released September 13, 1999, updated March

24 2000.

-

Joy Gordon, Economic

sanctions as a weapon of mass destruction

This

site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State's Office

of International Information Programs.

IP

Home | Index to This

Site | Webmaster

| Search This Site

| Archives |

U.S.

Department of State

|

|

Iraqi

Oil Export Revenue and Oil-for-Food Purchases a

Chart 1: Revenues from oil

sales continue to increase under the oil-for-food program, yet the Iraqi

regime refuses to use them to buy food for its people. (Phases

of the Oil-for-Food program: Each phase lasted 6 months, phase I started

on Dec. 10, 1996. Dividing the Money)

|

|

IV.

2. a Iraq

Didn't Agree to Targeted Sanctions

" the need to regain

the moral high ground given the widespread criticism that sanctions have

caused a humanitarian disaster. Most efforts have centred on developing

more targeted sanctions while simultaneously improving the provisions for

humanitarian aid. The British Government played a constructive part in

this process by negotiating UN Security Council resolution 1284,

17 December 1999 [24].

This resolution provided for sanctions to be suspended for renewable periods

of 120 days so long as Iraq co-operated with a new UN Monitoring, Verification

and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) to replace UNSCOM.[25]

The resolution also lifted the ceiling on the volume of Iraqi oil exports

for humanitarian purchases, while easing the import of some agricultural

and medical equipment. Although the UK government signalled that resolution

1284 would restore international consensus on Iraq, only the UK and the

US voted in favour, while Russia, China and France all abstained. This

fragmentation might explain why Iraq rejected resolution 1284.

17. The UN again attempted

to resolve this crisis in November 2001 with UN Security Council resolution

1382 [26].

Resolution 1382 restates the central provisions of resolution 1284 that

suspension of sanctions remains dependent on Iraq's compliance of its obligations

under UN resolutions and its agreement to co-operate with UN weapons inspectors.

In addition, the resolution contains arrangements for targeted controls

on Iraq by introducing a Goods

Review List, under which Iraq would be free to meet all of its civilian

needs, while making more effective the existing controls on items of concern,

such as military and WMD related goods. According to the UK Foreign Secretary:

"The UN decision will soon mean no sanctions on ordinary imports into Iraq,

only controls on military and weapons related goods. Iraq will be free

to meet all its civilian needs. The measures leave the Baghdad regime with

no excuses for the suffering of the Iraqi people." [27]

In addition, the resolution aims to build greater co-operation with Iraq's

neighbours through an expanded trade regime. This resolution came into

force on 30 May 2002. The expanded trade regime is especially important

to strengthen the waning support of those countries like Jordan and Turkey,

which have experienced significant trade diversion as result of the sanctions

regime. This trade diversion has encouraged an illicit cross border trade,

the depth of which remains uncertain.

18. The Iraqi Government has

consistently refused to accept these new resolutions. Iraqi foreign policy

is driven by the attainment of two goals—an end to sanctions and the survival

of the regime. Its skilful manipulation of the concerns of the original

members of the Gulf War coalition has seriously, and perhaps terminally,

undermined the present sanctions regime.

IV.

2. b Saddam's Obstruction

The Iraqi government obstructs the

Oil-for-Food program (OFF) and diverts goods delivered under OFF. http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/nea/iraq/text/0912wthsbkgd.htm#efforts

Source: Chart

2 of U.S. Department of State paper "Iraqi

Obstruction of Oil-For-Food".

Additions (thin lines) by J.

Gruber with data from Table 1, Global trends in 5-year estimates of

under-five mortality rate, 1955?99, and WHO estimates for 1999, O,B. Ahmad, A.D. Lopez, M. Inoue, The

decline in child mortality: a reappraisal, Bulletin of the World Health

Organization, 2000, 78 (10):1175-1191.

-

Stark evidence of the government's callous

policies was documented in a recent UNICEF survey, which found that child

mortality rates doubled in South and Central Iraq, where Saddam Hussein

controls distribution of humanitarian assistance, but child mortality rates

actually dropped in the North, where the UN controls distribution. http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/nea/iraq/iraq99i.htm

-

We are proposing that the U.N. Sanctions

Committee on Iraq review requests for medications that might have military

use when the requests are for quantities that are grossly in excess of

any civilian requirement. The United States opposes allowing the Iraqi

military to stockpile quantities of certain medicines that could be used

to protect its troops in the event Iraq launched chemical or biological

warfare. http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/nea/iraq/text/1221fact.htm

-

The United Nations has reported that $200 million worth of medicines and medical supplies sit undistributed in Iraqi warehouses. This is about half the value of all the medical supplies that have arrived in Iraq since the start of the oil-for-food program.

-

http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/nea/iraq/iraq99b.htm,

-

http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/nea/iraq/chart1.htm,

-

von Sponeck

sees multiple

reasons for that.

American Friends Service Committe (AFSC), Iraq

Timeline (in cache)

- 1997 - UNICEF reports that more than 1.2 million people, including 750,000 children below the age of five, have died because of the scarcity of food and medicine.

- 1998 - A 1998 World Health

Organization (WHO) report states that each month, out of the 5.2 million

Iraqi children under 5 years of age between 5,000 and 6,000 children die

because of sanctions.

Oil-for-Food

Goods Remaining Undistributed in Iraq

Chart 3: The Iraqi Government

has refused to distribute to the people of Iraq billions of dollars worth

of supplies delivered by the oil-for-food program.(Source: Iraqi

Obstruction of Oil-For-Food)

|

version: September 10, 2013

Address

of this page

Home

Joachim

Gruber