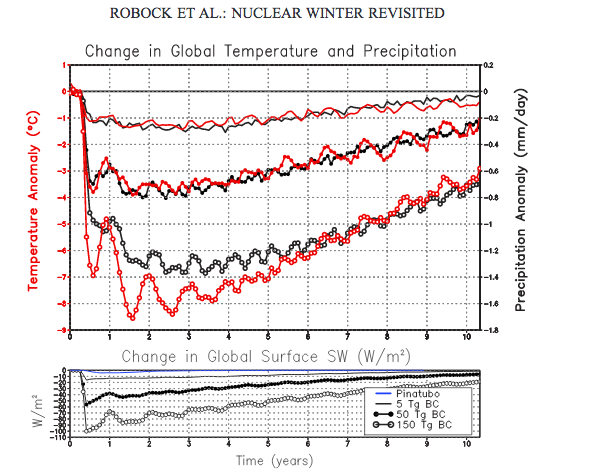

Figure 2: Change of global average surface air temperature (red curves), precipitation (black curves), and net downward shortwave radiation when smoke (black carbon (BC)) is mobilized by small, moderate and large portions of the current (2007) global arsenal of nuclear weapons. Three cases are considered (1 Tg smoke = 106 t smoke = 1 Megaton smoke):

- upper curves (lines) - small portion of global nuclear arsenal: 5 106 t black carbon [Robock et al., 2007],

- middle curves (filled circles) - moderate portion of global nuclear arsenal: 50 106 t black carbon, and

- lower curves (empty circles) - large portion of global nuclear arsenal: 150 106 t black carbon.

Also shown for comparison is the global average change in downward shortwave radiation for the 1991 Mt. Pinatubo volcanic eruption [Oman et al., 2005], the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

The global average precipitation in the control case is 3.0 mm/day (1095 mm/year), so the changes in years 2Ð4 for the 150 106t case represent a 45% global average reduction in precipitation.

Source: Fig. 2 of Alan Robock et al., "Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences"

(see for comparison Owen B Toon (Univ Colorado Boulder), Charles Bardeen (National Center for Atmospheric Research), Alan Robock (Rutgers University), "Rapid Expansion of Nuclear Arsenals by Pakistan and India Threatens Regional and Global Catastrophes", American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting, Washington DC, 10 - 14 Dec. 2018, in cache)

|

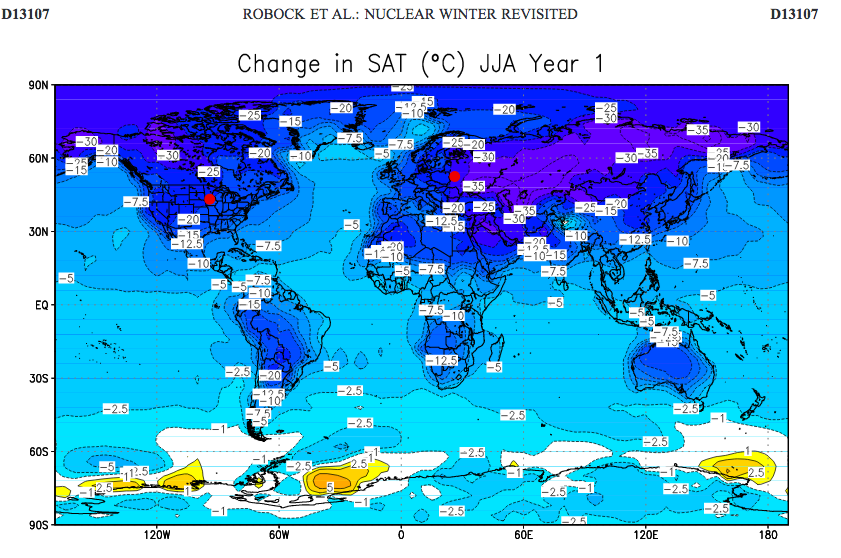

Figure 5: Surface air temperature (SAT) changes for the 150 106 t BC case averaged for June, July, and August in the year following the year of smoke injection. Effects are largest over land, but there is substantial cooling over oceans, too. The warming over Antarctica in year 0 is for a small area, is part of normal winter interannual variability, and is not significant. Considering that the global average cooling at the depth of the last ice age 18,000 years ago was about -5 C, this would be a climate change unprecedented in speed and amplitude in the history of the human race. Source: Fig. 5 of Alan Robock et al., "Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences" |

|

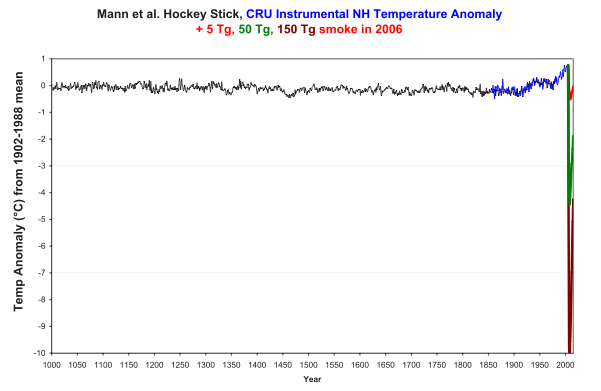

Figure 9: Northern Hemisphere average surface air temperature change from 5 Tg (red), 50 Tg (green), and 150 Tg (brown) cases in the context of the climate change of the past 1000 years. The "hockey stick" nature of the curve is barely discernible when plotted on this scale. Black curve is from Mann et al. [1999], and the blue curve is from the latest data from the Climatic Research Unit website. Mann, M. E., R. S. Bradley, and M. K. Hughes (1999), Northern Hemisphere temperatures during the past millennium: Inferences, uncertainties, and limitations, Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 759Ð762. |

end of inserted text

It is the smoke, after all (not the fallout, which would remain mostly limited to the northern hemisphere), that would do it worldwide: smoke and soot lofted by the fierce firestorms in hundreds of burning cities into the stratosphere, where it would not rain out and would remain for a decade or more, enveloping the globe and blocking most sunlight, lowering annual global temperatures to the level of the last Ice Age, and killing all harvests worldwide, causing near-universal starvation within a year or two.

U.S plans for thermonuclear war in the early sixities, if carried out in the Berlin or Cuban missile crises, would have killed many times more than the 600 million people predicted by the JCS. They would have caused nuclear winter that would have starved to death nearly everyone then living: at that time 3 billion [3000 million].

The numbers of warheads on both sides have since declined greatly -by over 80%- from their highest levels in the 60s. Yet the most recent scientific calculations -confirming and even strengthening the initial warnings of more than 30 years ago- even a fraction of the existing smaller arsenals would be more than enough to cause nuclear winter today, on the basis of existing plans that target command and control centers and other objectives in or near cities.

In other words, first-strike nuclear attacks by either side very much smaller than were planned in the 60s and 70s -and which are still prepared for instant execution in both Russia and America- would still kill by loss of sunlight and resulting starvation nearly all the humans on earth, now over seven billion.

... There is no sign that the findings of the latest scienctific peer-reviewed studies of climatic consequences of nuclear war over the past decade have penetrated the consciousness of U.S. officials or Russian officials or have influenced in any way their nuclear deployments or arms-control negotiations.

There is good reason to doubt that either George W. Bush or Barack Obama -or, for that matter, George H.W. Bush or Bill Clinton in the previous 20 years since the original studies- was ever, once, briefed on the scale of this result of the large "options" he was presented with in nuclear command exercises. (Gorbachev has reported that he was strongly influenced by Soviet studies of this phenomenon, which underlay his desire to seek massive reductions and even the elimination of nuclear weapons in the discussions with Reagan, who made a similar attribution.)

Whether or not President Trump has been briefed on this (almost surely not), both he and several of his cabinet officials, along with leaders of the Republican majority in Congress, are famous deniers of the scientific authority of such findings, based as they are on the most advanced climate models.

Chapter 2

Command and Control - Managing Catastrophe

pages 64 - 66

[During my time at RAND] There was no Stop or Return code in the envelope or otherwise in the possession of the [American attacking air] plane crew. Once an authentical Execute order had been received, there was -by design, it turned out- no way to authenticate an order to reverse course from the president or anyone else. And no such unauthenticated order was to be obeyed.

There was no officially authorized way for the president or the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff] or anyone else to stop planes that had received an Execute order -whether they had just taken off or had passed beyond their positive control line- from proceeding to the target and dropping their bombs. From that point on, the planes, whether tactical or strategic, could no more be called back by the president or any subordinate from their attack project than a ballistic missile. This despite the fact that for many SAC [Strategic Air Command] planes launching from the United States, the remaining time before they reached their assigned targets after receiving an Execute order might be 12 hours or more: time enough for world history and the framework of civilization to have altered decisively since the initial order, whether by nuclear explosions, coups in the Sino-Soviet bloc, or convincing offers of Soviet surrender, not to mention the discovery of a terrible error.

But that meant there would also be time enough after issuance of an Execute order -as several high-level staff officers told me their superiors worried about- for a presidential change of mind. Fear of that contingency was not the first explanation to be proposed by a control officer for the absence of a Stop or Return order from the authentication envelopes. ... The ... reason given to me in 1960 was that "the Soviets might discover the Stop code and misdirect the whole force back". This is precisely the explanation given to the president in Dr. Strangelove for his lack of ability to send a Stop order to the planes that have been lauched by the mad base commander General Jack D. Ripper.

I was dumbstruck by the realism of this point, among others, when I first saw the movie in 1964 [Dr. Strangelove is basically a documentary, in cache)]. Harry Rowen and I had gone into D.C. from the Pentagon during the workday to see it "for professional reasons". We came out into the afternoon sunlight, dazed by the light and the film, both agreeing that what we had just seen was, essentially, a documentary. (We didn't yet know -nor did SAC - that existing strategic, operational plans, whether for first strike or retaliation, constituted a literal Doomsday Machine, as in the film.)

How, I wondered, had the filmmakers picked up such an esothercic, highly secret (and totally incredible) detail as the lack of any physical restraint on the ability of a squadron commander, or even a bomber pilot, to execute an attack without presidential authorization? It turned out that Peter George, one of the screenwriters and the author of Red Alert, the novel on which the film was based, was a former Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command flight officer. That suggests the Bomber Command's Êcontrol system had the same peculiar characteristics as SAC's. And probably for the same underlying reasons.

The real concern, I was told privately by more than one credible staff officer - amog others, by Lieutenant Colonel, later Major General, Bob Lukeman in the Air Force office for war plans - was that a civilian president or (if the president were unavailable or Washington was destroyed) some civilian deputy, on whatever basis, might have second thoughts about the attack under way after an Execute order had been sent, and try either to modify it midway or cancel it. At best, he would be passing up the opportunity for a coordinated surpride attack, and at worst, leaving our fores totally disorganized and vulnerable - along with the country - to an enemy attack either already under way or launched as soon as the enemy had detected and figured outÊwhat had just happened on our side.

That's the exact argument of General Buck Turgidson, played by George C. Scott in Dr. Strangelove, against the president's attempting to recall all the planes that General Ripper had launched toward Russia. It represented fairly the view to be expected in such a situation from any number of Air Force officers, high or low. As the major in Kunsan had put it to me, "If one goes, they might as well all go."

Whether or not this distrust of high-level civilian readiness to initiare nuclear war -which I encountered over and over in my experience in the Pentagon- was a key motive for the absence of a card with a Stop code in the envelopes of the alert forces, it was a fact that the systems designed and operated by tne military assured the practical inability of the president or any civilian to reliably stop any bombers from carrying out attacks once they had received authenticated Execute orders (from whomever). Nor could the president then or now -by exclusive possession of the codes necessary to launch or detonate any nuclear weapons (no such exclusive codes have ever been held by any president)- physically or otherwise reliably prevent the JCS or any theater military commander (or, as I've described, command post duty officer) from issuing such authenticated orders. That is, of course, contrary to the impression given to the public by every president up to the present. The impression is false, as I was to discover.

Chapter 6

The War Plan - Reading the JSCP

pages 90 ff

In the course of my work in the Pacific, I had several discussions with Dr. Ruth M. Davis, who was in charge of computer development for CINCPAC. She was one of the highest-ranking civilians working directly for the military anywhere. When I described some of the puzzles and startling characteristics of the plans I was reading, she told me, in great confidence, of a plan she said I should see if I wanted to understand the nature of U.S. nuclear war planning. It was called the JSCAP (pronounced "J-SCAP"), for Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan, and it was on this that the president did not know of the nature or even the existence of the JSCAP, nor did any other civilian authority. That was confirmed for me by an officer in the war plans division of the Air Force, Lieutenant Colonel Bob Lukeman, who eventually lent me a copy to read in the Pentagon.

To understand how there could be a top-level nuclear war plan of which the secretary of defense had no awareness, it's necessary to know something of the history of the relationship between the secretary of defense and the military. Prior to 1947, when the National Military Establishment, renamed in 1949 the Department of Defense, was created -combining the Department of War (Army) and Navy, with the Air Force emerging from the Army as an independent service- there was no secretary of defense. The responsibilities of the secretary of defense gradually evolved over the next decade. Before 1958, the secretary of defense and his assistant secretaries on the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSI) were seen as functioning essentially in nonoperational areas such as procurement, research and development, personnel, and budget, and not as having responsibilities or command powers in direct areas of combat operations or planning.

Thus, a secretary of defense like Charles Wilson might or might not be in on high-level crisis discussions and decisions, such as the Quemoy crisis of 1954-55. The record of this early period shows that the secretaries of defense were sometimes present in crucial meetings and sometimes not. It depended on their personalities and their relationship with the president. During the whole early era of the institution of this office, the JCS had a basis for saying that the secretary and his subordinate staff had no "need to know" operational war plans, since he was not involved in the operational command.

In 1958, however, the Reorganization Act put the secretary of defense directly in the chain of command, second to the president as a link to the unified and specified commanders and their subordinate commands. (A unified commander was, essentially, a theater commander who, as in the Pacific or Europe, had elements from different services under his command. A specified commander -there was only one, the Strategic Air Command- had units from just one service.) This act cut the JCS out from the chain of command. It was President Eisenhower's specific intent to do that. He had no respect for the JCS as a body, having dealt with them as Army chief of staff and later as the supreme commander in Europe. He was particularly disillusioned with their postwar performance and wanted to abolish them entirely. However, they were preserved mainly by Congress, which wrote into the Reorganization Act that, without being in the chain of command, the JCS should serve as the "principal military advisors" to the president.

The secretary of defense at the time of the 1958 act was Neil McElroy, who had been CEO at Procter & Gamble. He was said to be a very intelligent man, but he had no background in military matters and he put in an unusually short workday beause he tended to his sick wife. Thus, as I was later told by Air Staff officers, it was relatively easy for the JCS to manipulate him. They got McElroy to sign a Department of Defense directive that reinterpreted the legislated act: "The chain-of-command is from the President as Commander-in-Chief, to the Secretary of Defense, to the Unified and Specific Commanders, through the Joint Chiefs of Staff" (emphasis added). This implied that the Joint Chiefs would be, in some sense, a channel for his directives. They further got him to agree, as a practical matter, to delegate all operational responsibilities to them. In effect, the act and President Eisenhower's intentions were circumvented. Although it was still on the books, it resulted in no real change of operating responsibilities in 1958 or 1959.

Secretary Thomas Gates, who succeeded McElroy under Eisenhower, had much stronger instincts to exercise control. Yet, with respect to the Office of the Secretary of Defense -comprising the secretary and his staff but also all the deputy and assistant secretaries and their staffs- the JSCP was and remained what later secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld would have called an "unkown unkown": something they didn't know they didn't know about.

In fact, I was to learn, the JCS had formally adopted, in writing, a set of practices designed to keep the secretary of defense from ever asking any questions directly about the general war plan. The first protective practice was to call the annual war plan the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan, which did not betray to a layman that it had to do with current operations or, more specifically, with current nuclear war targeting. It was usually referred to by its initials JSCP, but the JCS had issued a directive in writing, which I read, that the words "Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan, or the capital letters JSCP, should never appear in correspondence between the JCS and any agency of the Office of the Secretary of Defense".

Any JCS staff papers to be referred to the secretary of defense or his office were to be retyped to eliminate any possible references to the JSCP. If there was an absolute need to refer to such plans in some oblique fashion, the directive continued, reference was to be made to "capabilities planning" (lowercase), which would, again, not suggest the existence of a specific plan or suggest that it was any kind of war plan at all.

That phrase -no less than the official title, Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan- was a euphemism, a cover. It was meant to obscure from the secretary -and more important, from his deputy and assistant secretaries and their civilian staffers- that there existed a single highest-level annual operational plan for the conduct of general and limited war, the authoritative guidance for all lower-level operational war plans.

page 93

All this was intended to preempt the JCS nightmare: that the secretary or a civilian working for him might see this acronym in a document, might ask what it meant, and then ask to see the plan. This could open the possibility of civilians working for the president actually reviewing the plan and demanding changes. A vague reference to "issues arising in capabilities planning", which the JCS directive prescribed, gave such officials no handle to ask for a specific document, or a hint that there was an overriding piece of paper that would be worth their while to read.

As a result, almost no civilian, including the secretary of defense, was aware that a piece of paper of the character of the JSCP existed. That, of course, extended to its critical "Annex C" -the SAC war plan, which laid out in some detail the nature of our general (nuclear) war operations. The JSCP stated, "In the event of general war, Annex C would be executed."

Reading that statement by itself, knowing what Annex C was, one might naturally infer that that provision virtually defined "general war", in operational terms. It was when the president would direct that the SAC war plan, attached, should be executed against our principle adversary, the Soviet Union. But when might he do that?

...

page 94

In fact, an explicit definition of "general war" did appear in the JSCP. This was perhaps the most sensitive piece of information in the entire document, and the main reason for protecting it from the eyes of civilian authority. ... "General War is defined as armed conflict with the Soviet Union."

To properly understand the hair-raising import of this proposition, one has to read it in the context of two other key assertions in the JSCP: "In general war, Annex C will be executed"; and "in general war, a war in which the armed forces of the USSR and of the U.S. are overtly engaged, the basic military objective of the U.S. Armed Forces is the defeat of the Sino-Soviet Bloc.

The meaning of "armed conflict", in this case the key trigger to unleashing the full fury of the SAC war plan against both the Soviet bloc and China, was subject to some narrow controversy in military circles. ... It implied that any conflict pitting U.S. forces against any more than several battalions of Soviet troops anywhere in the world -Iran, Korea, the Middle East, Indochina- would lead to instant U.S. strategic attacks on every city and command center in the Soviet Union and China. It was hard to imagine that such a plan could actually be carried out. Yet according to what I had already come to discover in the Pacific, and what turned out to apply worldwide, no alternative plans existed for a war involving Soviet forces on a level beyond a division or two except for the general war plan. And that lack was by directive of President Eisenhower, who had decreed that there should be no plans for "limited war" with the Soviet Union, whether nuclear or conventional, under any circumstances, anywhere in the world.

This reflected Eisenhower's military judgment that no war between any significant forces of the United States and the Soviet Union could remain limited more than momentarily. Therefore if such a conflict were pending, the United States should immediately go to an all-out nuclear first strike rather than allow the Soviets to do so.

page 95

But even if those military judgments were challenged -as they were, repeatedly, by Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell Taylor- Eisenhower believed that any alternative approach was unacceptable from a fiscal point of view. Under the influence of conservative economic advisors, he was convinced that preparation to fight even a limited number of Soviet divisions on the ground (as Taylor proposed), with or without the use of tactical nuclear weapons, would compel an increase in defense spending that would cause inflation, precipitating a depression and "national bankruptcy".

...

Army leaders like Taylor, and initially those in the Navy as well, wanted to define "general war" as narrowly as possible, leaving a broad range of conflict situations to be planned for, budgeted for, and addressed if they arose, without necessarily involving an attack by SAC on the Soviet Union or China. They argued, with a good deal of plausibility, that since such an attack involved a high risk, if not a certainty, of devastating retaliation against the United States, it should be reserved for only the most extreme, exigent contingencies.

...

page 96

The Army and Navy didn't give up. though they continued to be overruled. In my notes of the Army and Navy view as of October 30, 1959, general war should be defined as "governmentally directed overt armed conflict between nations with the objective of complete subjugation or destruction of the national entity of the enemy", with other forms of armed conflict, including between U.S. and Soviet forces, characterized by "limitations on locale, weapons, forces, participants, or objectives".

...

My friend Colonel Ernie Cragg in Air Plans was pointing out in dueling memos with the Army as late as January 21, 1961 (the day after Kennedy's inauguration):

Adoption of the "view" that limited wars between the US and the USSR are possible is an "invitation" to attack. It also could open Pandora's box with respect to forces for limited war at the expense of general war forces. ... It would allow the Army and Navy to increase their "requirement" for forces for limited war to almost unlimited levels.

page 97

... Since there was to be only one plan for fighting Russians anywhere in the world under any circumstances -including, along with SAC, Polaris submarines, and theater forces- Eisenhower endorsed in 1959 the coordination of a single strategic plan at SAC headquarters in Omaha. Annex C of JSCP came to be, by December 1960, the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP).

By 1960, the planners of the SIOP, the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff, had gathered all the general-war target lists of the various commands, including SAC, NATO, and PACOM, into one coordinated target list to allocate weapons more efficiently to targets all over the world. ...

Again, there was an intense concern for minimizing the "interference" or "fratricide" of vehicles aimed at targets in close proximity. There was also a desire by Eisenhower to reduce "duplication" of efforts by different commands. In the actual planning, both concerns were totally frustrated; the latter because each command and service was determined to cover important targets by its own forces. By some counts, over 80 weapons were dedicated to Moscow; other counts put this at 180. Meanwhile, the prevention of "interference", as in the Pacific, remained a delusional objective.

page 98

As with the CINCPAC plan I had read earlier, the coordination involved in this higher-level plan was so complex that there was room for only one real strategy. The price of bringing all the theater and component service plans into harmony with each other, into one plan, was the total elimination of any flexibility in carrying it out. So much planning was involved in producing this one scenario that there was simply no staff or computer time available to produce an alternative. As with CINCPAC planners I met earlier, the SIOP planners themselves were appalled at the confusion and chaos that might ensue if any alternative was proposed.

Following the guidance of the JSCP, the planners at SAC headquarters set out to weld all the warheads in the U.S. arsenal into one hydra-headed monster that would arrive on its targets as near simultaneously as possible, preferably before any Soviet warheads had launched.

On strips like Kunsan or Kadena and on aircraft carriers surrounding the Sino-Soviet bloc (as it was still described in 1961, though China and the Soviets had actually split apart a couple of years before that), more than 1000 tactical fighter-bombers were armed with H-bombs in range of Russia and China. Each of them could devastate a city with one bomb. For a larger metropolitan area, it might take two. Yet until this time, SAC planners had regarded these tactical theater forces as so vulnerable, unreliable, and insignificant a factor in all-out nuclear war that they had not even bothered to include them in calculating the outcome of attacks in a general war.

In 1961 there were about 1700 SAC bombers, including over 600 B-52s and 1000 B-47s. In the bomb bays of the SAC planes were thermonuclear bombs .... from 5 to 25 Mt in yield. Each 25 Mt bomb ... was the equivalent of over 12 times the total tonnage we dropped in World War II. Within the arsenal there were some 500 bombs with an explosive power of 25 Mt. Each of these warheads had more firepower than all the bombs and shells exploded in all the wars of human history. ...

page 99

The preplanned targets for the whole force included, along with military sites, every city in the Soviet Union and China. There was at least one warhead allocated for every city of 25000 people or more in the Soviet Union. The "military" targets (many of them in or near cities, and many only tendentiously described as military) were by far the great majority, since all the cities could be totally destroyed by a small fraction of the attacking vehicles.

In 1960 - 61 it was in reality quite possible -though USAF and CIA "missile gap" estimates implied otherwise- that not a single nuclear warhead would land on U.S. territory after such an American first strike. Worldwide fallout in the stratosphere from our own strikes would certainly kill Americans, but over so long a time, with radioactivity decaying in the atmosphere on the way over and deaths from cancer long delayed, that the increase in mortality in any one year might not be statistically perceptible. But our Western European allies in NATO would be quickly annihilated twice over: first from the mobile Soviet medium-range missiles and tactical bombers targeted on them, which our first strike couldn't find and destroy reliably, and second from the close-in fallout from our own nuclear strikes on Soviet bloc territory.

John H. Rubel's brief memoir provides a vivid account of the first high-level presentation on the completed SIOP-62 by one of the handful of civilians who was present on that historic occasion. I quote his description at length, because I don't know of anything else like it in print from an insider. Rubel is the only person exposed to the SIOP who has recorded, in his comments toward the end, the same emotional reaction to it that I experienced a few months later in the White House when I saw the JCS extimate of the death toll from our own attacks.

page 102

... The briefing [on the Soviet Union] was soon concluded, to be followed by an identical one covering the attack on China given by a different speaker. Eventually, he too arrived at a chart showing deaths from fallout alone. "There are about 600 million Chinese in China." he said. His chart went up to half that number, 300 million, on the vertical axis. It showed that deaths from fallout as time passed after the attack leveled out at that number, 300 million, half the population of China.

A voice out of the gloom from somewhere behind me interrupted, saying. "May I ask a question?" General Power turned again in his front-row seat, stared into the darkness and said, "Yeah, what is it?" in a tone not likely to encourage the timid. "What if this isn't China's war?" the voice asked. "What if this is just a war with the Soviets? Can you change the plan?"

"Well, yeah", said General Power resignedly, "we can, but I hope nobody thinks of it, because it would really screw up the plan."

...

page 103

One person, alone, at the second session raised objections. It was the commandant of the Marine Corps, David M. Shoup, who had earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for commanding from the beach the Marines who landed at Tarawa. ...

"All I can say is", [Shoup] said in a level voice, "any plan that murders 300 million Chinese when it might not even be their war is not a good plan. That is not the American way."

It was, however, the American plan. Though President Eisenhower was distressed when his science advisor George Kistiakowsky reported to him the tremendous amount of "overkill" in the plan, Eisenhower endorsed the plan and passed it on without any modification to John F. Kennedy a month later. It was my passion to change it.

Chapter 8

"My" War Plan

page 124

... My personal hope was that higher-level, civilian scrutiny of those plans could eliminate or at least greatly reduce the probability of the particular insanities that involved targeting China in all circumstances of war with the Soviet Union, and of automatically targeting cities en masse either in China or the USSR. By emphasizing the importance of witholding reserve forces (which meant mainly city-busting Polaris missiles) and withholding initial attacks on cities, I privately hoped to avert or minimize attacks on cities altogether, whether we struck preemptively or in return.

Such an approach called for drastic changes in both plans and preparations from the posture that had developed since 1953, culminating in 1960. For that reason it seemed clear that the new [Basic National Security Policy] BNSP should be drafted in considerable concrete detail, rather than being the brief and vague document which the military had come to expect in the years when it simply reaffirmed the existing New Look doctrine, which emphasized reliance on nuclear weapons, both strategic and tactical, largely for long haul budgetary reasons. ...

page 125

... to avoid the previous ambiguity of the meaning of "general war", Kaufmann and I agreed in our drafts to use the term "central war" (a RAND term), as distinguished from "local war" (instead of "limited war"). "Central war" was defined in my draft (later signed by McNamara) as "war involving deliberate nuclear attacks, instituted by government authority, upon the homelands of one or both of the two major powers, the United States and the Soviet Union". ... There was no longer in our guidance a concepts of "general war" defined simply as "armed conflict with the Soviet Union".

Local war was defined in our drafts as "any other armed conflict". The previous JSCP concept of "limited war" -as distinct from war with the Soviet Union- was discarded because we proposed to aim at limiting if possible, even hostilities with the Soviet Union, even in central war. ...

page 126

To an uninformed reader -nearly everyone outside the actual nuclear planning process, including the secretary of defense and the president- these proposed policies would probably appear commonsensical. And so they were, except for the fact that almost every sentence constituted a radical challenge to and departure from some fundamental characteristic of the then-existing plans and preparations. For instance

- My proposal to retain a strategic reserve (particularly of the city-busting Polaris missiles) ran completely counter to the previous plan, in which all ready vehicles, including the Polaris missiles, were committed to preplanned targets as soon as possible.

- My insistence on the importance of maintaining reliable command and control ran against the notion that unauthorized "initiative" might be necessary, either at high military levels of command or at low, an attitude that increased the possibility of unauthorized "initiative" in a time of crisis, under the stress of ambiguous indications or an outage of communications with higher command.

- While there existed physical safeguards against accidents, there had been almost none against unauthorized action, either in connection with individual vehicles or in command post operations. I proposed that such safeguards could take the form of a combination lock on weapons, requiring a code sent by higher authority to unsafe or release the weapon (some form of [Permissive Action Links] PALs).

- The rigid SIOP provided for no distinction between the USSR and China; it allowed for no option or postponement of attacks on cities; it offered no option for preserving enemy command and control capability. In contrast, I called for flexible contingency planning that allowed for all these options.

- Existing planning allowed for no Stop order once an authenticated Execute order was received by [Strategic Air Command] SAC forces. Since this unleashed attacks on all major Sino-Soviet urban-industrial centers and governmental and military control centers, this policy maintained no plausible basis for inducing any Soviet commanders or units to terminate operations prior to expenditure of all their weapons upon the U.S. and allied cities. I proposed that a secure system of command and control was necessary to allow the option of limiting or terminating a conflict before all our forces were deployed, with reliable "stop" or "recall" orders.

page 127

All this was laid out in a memo for Harry Rowen, Paul Nitze, and Secretary of Defense McNamara, listing some of the limitations of the current plans that I intended to redress.

A second memo listed some of the changes my draft guidance called for:

- elimination of the SIOP as a single, automatic response in central war;

- elimination of the automatic inclusion of China and Soviet satellite states;

- plans to withhold some survivable forces, and an initial avoidance of enemy cities and governmental and military controls;

- the requirement of a survivable, flexible command and control system, headed by the president or as high an authoritative figure as possible;

- an effort to induce the enemy to terminate war by not destroying all major urban-industrial areas at the outset;

- plans and preparations to use conventional weapons in local conflict, up to large-scale conflict (in addition to plans to use nuclear weapons);

- rejection of any single, inflexible plan to be adopted for use in a wide range of circumstances of central war (let alone the SIOP) or that any given set of targets should be marked for immediate, automatic destruction under all circumstances of central war; and

- rejection of the inevitability of central war in war with the Soviet Union.

page 128

...The final version, redrafted for Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric's signature, was sent to the JCS chairman on May 5, 1961, with the heading "Policy Guidance on Plans for Central War", along with my draft portion of the proposed BNSP. (For texts of all these memo and drafts, go to this address)

"My" revised guidance became the basis for the operational war plans under Kennedy -reviewed by me for Deputy Secretary Gilpatric in 1962, 1963, and again in the Johnson administration in 1964. It has been reported by insiders and scholars to have been a critical influence on U.S. strategic war planning ever since.

Years later, when I mentioned to a friend that I had finished my first draft of the Top Secret guidance to planning for general nuclear war on my thirtyieth birthday, his uncharitable reaction was, "That's frightening". I said, "True. But you should have seen the plan I was replacing." In years to come, the memory of this accomplishment did not bring me the same satisfaction it brought when I was thirty.

Chapter 9

Questions For The Joint Chiefs: How Many Will Die?

pages 129 ff

In the spring of 1961, Harry Rowen told me that after a briefing to McGeorge Bundy im January, Bundy had called the director of the Joint Staff of the JCS and asked him to "send over a copy of the JSCP".

The director told him, "Oh, we can't release that."

Bundy said, "The president wants to read it."

The director said, "But we've never released that. I can't."

Bundy told him, "You don't seem to be hearing me. It's the president who wants it."

"We'll brief him on it."

Bundy said, "The president is a great reader. He wants to read it."

It was finally agreed, Harry told me, that the president would get the JSCP and a briefing by a member of the Joint Staff.

Soon after I had finished drafting the basic national security policy, Rowen and I were talking to the Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric in his office in the Pentagon, and Gilpatric remarked to me, "By the way, we finally got the JSCP". He said that instead of sending it over to the White House, the Joint Staff had finally negotiated that they would give a briefing on it in Gilpatric's office. McNamara had attended, and McGeorge Bundy came over from the White House.

I asked him if they had seen an actual copy of the plan after all. He said yes, the briefer had left the plan with him. I asked if I could see it. Gilpatric led us into his safe. Instead of a safe with drawers, he had a long closet that had been converted into a bank-like vault with a heavy steel door. It had a tall ceiling and reinforced walls lined with library shelves filled with documents stamped "Top Secret" and higher. He found a document lying on one of the shelved near the front and handed it to me.

At a glance, it didn't look to me like the JSCP, because it was typed on regular 8x10 inch paper, not the heavier 11x14 inch legal-size pages of a finished JCS document. Well, I thought, they might have just retyped it on regular-size paper for the deputy secretary. I looked immediately for the key section that appeared nowhere else but in the JSCP, the part the JCS had taken such care to withhold from civilians, the definition of "general war".

It wasn't there. There was no definition section, no definition of "general war" or "limited war". I looked to the first page and read the heading. It didn't say "Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan". It said "Briefing on the JSCP". Even that went beyond the terms of the earlier JCS directive I had seen, which told the Joint Staff that "neither the title Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan nor the initials JSCP are to be used in correspondence with the Office of Secretary of Defense". This heading broke that rule by using the forbidden initials "JSCP", apparently because Bundy's call to the director had revealed that that cat was out of the bag. Someone had leaked the acronym at least. But it wasn't yet clear to the Joint Staff that the White House or the Office of the Secretary of Defense knew more than the acronym -knew the contents of the plan and their implications- and the JCS hadn't yet given that up.

I told Gilpatric, "This isn't the JSCP. is this all they gave you?"

He looked taken aback, for once confused. He said, "Yes, it is. But I'm certain they told me it was the JSCP -they were leaving me a copy of the JSCP. Are you sure it isn't?"

I showed him the title. "It's not the JSCP. It's a copy of the briefing they gave you." I remarked on the size of the paper and told him about the crucial part that was missing. Evidently, they had left that out of the briefing. There might be more they had omitted.

Gilpatric seemed more embarrassed than angry. He said, "They told me they'd be glad to answer any questions we might have from the briefing and the paper. Would you take this and write out some questions for me to send to them?"

page 131

I took the briefing paper back to the room I was working in Rowen's suite of offices and put it in the safe. Then I walked down to an office in the Air Staff and asked Lieutenant Colonel Bob Lukeman, who had originally shown me the JSCP, if I could borrrow a copy again. I didn't tell him what it was for, and he gave it to me without any questions.

Within minutes I was back in my office with the paper that Bundy -speaking for the president- and the secretary of defense had been unable to get. There were, as before, some advantages to being from RAND. The Air Staff thought of us as one of them. That was why I'd been shown the JSCP the year before. But by this time, in 1961, Lukeman knew that I was a consultant to the secretary of defense, which would normally have meant (and did mean for the Air Force chief of staff) that I was working for "the enemy", as formidable an adversary as the Navy or Congress.

He had to have gotten in advance the approval of his immediate boss, Brigadier General Glenn Kent, for him to be showing me anything. I gathered that what was true for my friend the colonel must also be true for his boss. They disagreed with the policy embraced by the higher levels of the Air Force, wanted to see it changed, and were using me as a channel to the civilian authorities to make an end run around their own superiors.

I put the JSCP on a table next to the copy of the briefing paper from Gilpatric and began to compare them line by line. I made a list of the discrepancies and then began to lay out issues to be put to the JCS. I have my rough notes on questions for them. It took me a week of long days to finish them.

Some of these probed for the rationale of attacking cities and population en masse, immediately (or ever) and all -or for that matter, any- circumstances of war initiation. That was an aspect of the "optimum mix" concepts that was embodied in the SIOP. I asked:

- Why are major urban-industrial centers, or government controls, to be attacked concurrently with nuclear delivery capabilities?

- What national objectives require that urban-industrial centers be on the "minimum essential list" for intial attack? By what reasoning are these "essential"? What would be the costs, in terms of U.S. objectives, to omitting attack on these targets, relying upon residual strength to achieve objectives listed above?

- What is the distribution, by type, of targets in the satellite states? What contribution do they make to immediate Sino-Soviet bloc offensive capabilities?

- What is the total megatonnage dropped in the alert case? In the strategic warning case [full force]? What is the total of fission products? How much is air-burst, how much ground-burst? What would worldwide fallout be? What worldwide casualties?

- To what extent, and in what precise ways, does the planned attack upon urban-industrial centers and bonus targets differ from an attack intended to maximize population loss in the Soviet Union? In Communist China? In what ways will the execution of such attacks under the several conditions of war initiation, contribute to U.S. wartime or postwar objectives?

- Does the plan proceed on the assumption that it is national policy to hold the population of the USSR and Communist China repsonsible for acts of their governments? Are Communist Chinese people held reponsible for acts of the Soviet government?

page 132

Other questions pointed to the lack of flexibility in the planning, another aspect of the SIOP ("Annex C" of the JSCP, guidance for the operational plans of SAC and Polaris, not mentioned as such in the briefing):

- The plan provides for "optimum employment .... and the several conditions under which hostilities may be initiated". What are examples of those several conditions, other than Soviet surprise [nuclear] attack? How does the planned response differ for the different conditions? Is a single, uniform response optimal for all?

- Why do all options provide for total expenditure of the force? Why is no provision made for a strategic reserve?

- What is the ability of the JCS to accept the surrender of the enemy forces during the execution of the SIOP? What preparations have been made for this event? Have acceptable surrender terms been drafted? How reliable is the capability to STOP remaining attacks after Execute orders have been transmitted? Have preparations been made to monitor conformity to surrender terms?

page 133

Some of my questions couldn't possibly have occured to anyone simply from reading the briefing. I threw them in to warn the recipients that someone working for Gilpatric was already familiar with the problems of the operational planning:

- Does planned coordination assume that all offensive vehicles will get the Execute message simultaneously? If so, what is the estimated validity of this assumption? What will effects on coordination be of estimated lags in receipt of message? Or of different wind direction and strength affecting different parts of the attacking forces, in planning to avert interference?

Since these questions were supposedly coming from Gilpatric, who hadn't been given the JSCP, I had to find a way to draft them so that they would purport to be based only on the briefing paper that the JCS had given to him. But anyone who knew the actual plans would know that the person writing those questions was not Gilpatric. It had to be someone who was intimately familiar with the JSCP itself and all the controversies that lay behind it, who probably had a copy of it sitting in front of him. In other words, the Joint Staff and their bosses, the JCS, would know immediately that a copy of the JSCP had finally found its way to the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Moreover, they would know that someone who was either a military planner himself (a mole) or who had been very well educated by such planners was advising the deputy secretary.

The questions were the message. They were intended to leak into the JCS the news that their processes, their conflicts, compromises, and maneuvers, had become transparent to the Office of the Secretary of Defense. I hoped they would figure the game was up; they had to come clean and give straight answers. They had to fear that any efforts to lie or evade would be quickly spotted by whoever wrote these questions. (He might actually know, through some direct channel, their inner discussions of how to deal with the problem of responding to Gilpatric.)

Each question, still more the whole set, was designed to convey that someone working for Gilpatric knew, as military staffers used to say, "where all the bodies were buried". It would be clear not only that "he knows the JSCP, and he's got a copy", but also that he knew, somehow, why it was written the way it was, where the controversies were, how they had been papered over, and all the other things that it would be hard or impossible for the JCS to explain or justify.

page 134

I dont't have the final memo that I submitted to Gilpatric, in which the questions were more elegantly phrased than above. To keep up the pretense (however transparent to the recipients) that the questions were based on the briefing to Gilpatric rather than on the JSCP itself, most of my thirty or so queries started with reference to a statement in the briefing paper and then presented a list of sub-questions purporting to relate to it. I happen to recall verbatim the wording of the first question:

You say, on page 1, that each operational plan is submitted for review and approval to the next higher level of command.

- Was the JSCP sumbmitted to Secretary of Defense Gates for his review and approval?

- When in the annual planning cycle, is it customary to submit the JSCP to the Secretary of Defense for his review and approval?

True answers would have been (a) NO; and (b) Never. It was obvious that the drafter of the questions knew that. It was not obvious what a satisfactory explanation of those answers would be. Or those for the rest of the questions, which tended to get tougher from there.

When I handed the list to Gilpatric, he glanced through it, nodded his head, and said appreciatively, "These are very ... penetrating questions". He read it over more carefully, shook his head several times, thanked me warmly, and sent it off to the Joint Staff with a cover letter and without any changes.

There was no good way for the JCS or its staff to respond to these questions. If they lied or evaded, it was clear they would be found out. But if they answered truthfully, it would have seemed appropriate to send at the same time their letters of resignation. Bob Komer, McGeorge Bundy's deputy at the NSC, put that more strongly. After he read the draft I showed him in his office next door to the White House, he said to me, "If these were Japanese generals, they would have to commit suicide after reading these questions."

The generals and admirals who got the questions were not Japanese. They did not commit suicide, but they did get the message. Within hours of the questions being sent, the director of the Joint Staff was on the phone to Harry Rowen. As Harry told me, he asked very intensely: "Do you know anything about a set of questions we just received from Gilpatric?"

Harry said: "I might."

There was a long pause. Then a court "Who wrote them?"

Harry declined to say. End of conversation.

page 135

In a season when military staffs were working night and day to meet without fail or delay the secretary's short deadlines on numerous studies, this was the one set of questions that was simply never answered at all. ...

"That's perfect", Gilpatric told me, "we'll just leave them hanging there. Then if they fight us on the new plans, we'll just say, 'Well, then, let's go back to a discussion of your old plans'. And we'll start with those questions again."

Meanwhile, my revised quidelines on basic national security policy were signed by the secretary of defense, sent to the JCS as Secretary of Defense Guidance on War Planning, and eventually became the new policy. (President Kennedy had decided not to issue a new [Basic National Security Policy] BNSP in his own name.)

As it turned out, one of the questions I had drafted for Gilpatric got a different treatment. ... As recounted in the prologue (page 2), this question was the following: "If existing general war plans were carried out as planned, how many people would be killed in the Soviet Union and China alone?"

[Now, on pages 136 - 142, follows a detailed version of this paragraph of the prologue to the book]

The total death toll as calculated by the Joint Chiefs, from a U.S. first strike aimed at the Soviet Union, its Warsaw Pact satellites, and China, would be roughly 600 million dead.

in detail:

page 137

Fallout from our surface explosions in the

- Soviet Union,

- its satellites, and

- China

would decimate the populations

- in the Sino-Soviet bloc as well as

- in all the neutral nations bordering these countries -

- Finland.

- Sweden.

- Austria, and

- Afghanistan, for example - as well as

- Japan and

- Pakistan.

Given prevailing wind patterns, the Finns would be virtually exterminated by the fallout from surface bursts on Soviet submarine pens near their borders. These fatalities from U.S. attacks, up to another hundered million, would accur without a single U.S. warhead landing on territories of their countries outside the NATO and Warsaw Pact.

Fallout fatalities inside our Western European NATO allies from U.S. attacks against the Warsaw Pact would depend on climate and wind conditions. As a general testifying before Congress put it, these could be up to a hundred million European allied deaths from our attacks, "depending on which way the wind blows".

As I had intended, the JCS had clearly interpreted the phrase "if your plans were implemented as planned", to mean "if U.S. strategic forces struck first, and executed their planned missions without disruption from a Soviet preemptive strike". These figures clearly presumed that all or most U.S. forces had gotten off the ground with their weapons without having been attacked first. That is, it was implicit in these calculations -as in the greater part of our planning- that the United States would be initiating all-out nuclear war: either as escalation of a limited regional conflict that had come to involve Soviet troops or in preemption of a Soviet nuclear attack of which we had tactical warning. (The warning, it was understood, could be a false alarm. Or if it were not, the Soviet attack under way might be in response to a Soviet false alarm of a U.S. attack.)

page 138

The phrase "implemented as planned" referred to the assumption on which nearly all our planning was based: that in the whole range of circumstances in which nuclear war was likely to occur, we would "take the initiative". Before enemy warheads had arrifed or, perhaps, had been directed to launch, we would be striking first.

Thus, the fatalities the JCS were reporting to the White House were the estimated results of a U.S. first strike. The total death count from our own attacks, in the estimates supplied by the Joint Staff, was in the neighborhood of 600 million dead, almost entirely civilians. The greater part inflicted in a day or two, the rest over 6 months.

Army and Navy estimates of Soviet ICBMs threatening were "a few". But by all estimates, several hundred intermediate and medium-range missiles were aimed at Western Europe, Germany in particular, along with hundreds of medium-range bombers. Even after the most successful U.S. and NATO first strike, Soviet retaliation against Europe could have added a hundred million to the Western European death count from blast, fire, and immediate exposure to radiation even before the fallout from our own attacks had arrived from the east, borne on the wind.

page 148

In early July [1961], Alain Enthoven had arranged for me to have a brief luncheon with McNamara, to discuss my work on the guidance to the JCS on the war plan, which he had already approved and sent to the Chiefs. We ate at his desk, in his office. It was scheduled to last only half an hour, but it went on nearly an hour longer. I told him about the astonishing answers the JCS had given to the questions I had drafted in the name of the president, in particular about the effects they anticipated on our own European allies from their planned attacks on the Sino-Soviet bloc. I'd had no prior intention to bring up my own strongly heretical view on first use, but midway through our talk, he raised the issue himself.

There was no such thing as limited nuclear war in Europe, he said. "It would be total war, total annihilation, for the Europeans!" He said this with great passion, belying his reputation as a cold, computer-like efficiency expert. Moreover, he thought it was absurd to suppose that a supposedly "limited use" would remain limited to Europe, that it would not quickly trigger general nuclear war between the United States and Soviet Union, to disastrous effect.

I've never had a stronger sense in another person of a kindred awareness of this situation and intensity of his concern to change it. 30 years later, McNamara revealed in his memoir In Retrospect that he had secretly advised President Kennedy, and after him President Johnson, that under no circumstances whatever should they ever initiate nuclear war. He didn't tell me that, but it was implicit in everything he had said at this lunch. There is no doubt in my mind that he did give that advice, and that it was the right advice. Yet it directly contradicted the mad "assurances" on U.S. readiness for first use he felt compelled to give repeatedly to NATO officials (including speeches I drafted for him) throughout his years in office, as the very basis for our leadership in the alliance.

McNamara's assistant, Adam Yarmolinsky, had joined us for the last part of the lunch, without saying anything. When we left McNamara's office Adam took me into his small, adjoining room and said that he had never seen McNamara prolong a lunch that way. He had talked more frankly with me than Yarmolinsky had ever heard him talk with anyone else. The point of Adam's telling me this, and of my repeating it now, was to give weight to what he said next. "You must tell no one outside of this suite what Secretary McNamara has told you."

page 149

I asked if he was referring to fears of the reaction from Congress and the JCS (I could have added, "NATO"). He said, "Exactly. This could lead to his impeachment." I told him that I understood. But he went on to make that more explicit. "By no one", he said, "I mean, not Harry Rowen, not anybody." Now, that I understood. Evidently he knew that Harry was my closest friend and confidant, a cleared colleague with whom I normally would have shared even such sensitive information -though I'd been told not to tell anyone- unless I was specifically told not to. I never did tell anyone, not even Harry, what McNamara had said, though he would have found it as heartening as I did. But I did ask Adam one question: "As far as you know, is President Kennedy's thinking on these subjects different from the secretary's?"

Adam held up his thumb and forefinger pressed together, no space between them, and said, "Not an iota."

I left the secretary's suite thinking that here, in Robert McNamara, was someone whose judgement was worthy of my greatest trust. He had, as I saw it, the right perspective on the greatest dangers in the world, and the power and determination to reduce them. And he and his assistant had the street-savy to know that if he wanted to achieve that, he had to keep his cards very close to his chest.

... Dwight Eisenhower had secretly endorsed the blueprints of this multi-genocide machine. He had furthermore demanded, largely for budgetary reasons, that there be no other plan for fighting the Russians. He had approved this single strategic operational plan despite reportedly being, for reasons I now understood, privately appalled by its implications. And when the Joint Chiefs responded so promptly to the new president's questions about the human impact of our attacks, they clearly assumed that Kennedy would not, in response, order them to resign or be dishonorably discharged, nor order the machine to be dismantled. (In that, it turned out, they were right.)

Surely neither of these presidents actually desired ever to order the execution of these plans, nor would any likely successor. But they all must have been aware, or should have been, of the dangers of allowing such a system to exist. They should have reflected on, and trembled before, the array of contingencies

- accidents,

- false alarms,

- outage of communications,

- Soviet actions misinterpreted by lower commanders,

- unauthorized action,

- foolish Soviet initiatives or failure to comply with U.S. threats,

- escalation stemming from popular uprisings in East Germany or elsewhere in Eastern Europe

that might release these pent-up forces beyond their control or that, in ways they had not forseen, could lead them personally to escalate or to initiate a preemptive attack.

Eisenhower had chosen to accept these risks, to impose them on humanity and all other forms of life. Kennedy -and later, Johnson and Nixon to my direct knowledge- did likewise. There is much evidence that such catastrophic "major attack options" were among the choices offered to presidents Carter, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush, i.e., until the end of the Cold War. There is little known publicly about the range of options since then, although four hundred Minuteman missiles remain on high alert, along with a comparable number of Trident sub-launched missiles, each alert force more than enough to cause nuclear winter.

Moreover, I felt sure in 1961 that the existent potential for moral and physical catastrophe -our government's readiness to commit multi-genocidal extermination on a hemispheric scale by nuclear blast and fallout- was not only a product of aberrant Americans or a peculiarly American phenomenon. I was right. A few years later, after the humiliation of the Cuban missile crisis and the ouster of Khrushchev, the Russians set out to imitate our destructive capacity in every detail and surpass it where possible. By the end of the decade, they had succeeded. Ever since then, there have existed two Doomsday Machines, each on high alert and subject to possible false alarms and the temptation to preemption, a situation much more than twice as dangerous as existed in the early sixties.

... I personally knew many of the American planners, though apparently -from this fatality chart- not quite as well as I had thought. They were not evil, in any ordinary, or extraordinary sense. They were normal Americans, capable and patriotic. I was sure they were not different, surely not worse, than the people in Russia doing the same work, or the people who would sit at similar desks in later U.S. administrations or other nuclear weapons states.

I liked most of the planners and analysts I knew: not only the physicists at RAND who designed bombs and the economists who speculated on strategy (like me), but also the colonels who worked on these very plans, whom I consulted with during the workday and drank beer with in the evening. What I was looking at was not simply an American problem or a superpower problem. With the age of warring nation-states persisting into the thermonuclear era, it was a species problem.

A few years after leaving the White House, McGeorge Bundy wrote in Foreign Affairs, "In the real world of real political leaders -whether here or in the Soviet Union- a decision that would bring even one hydrogen bomb on one city of one's own country would be recognized as a catastrophic blunder; ten bombs on ten cities would be a disaster beyond human history; and a hundred bombs on a hundred cities are unthinkable."

In the last year of the Cold War, Herbert York cited Bundy's statement in a talk at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (of which he had been the first director), where, along with Los Alamos, all U.S. nuclear weapons had been designed. York posed the question, how many nuclear weapons are needed to deter an adversary rational enough to be deterred? Concurring with Bundy's judgment -as who would not?- he answered his question, "somewhere in the range of 1, 10, or 100 ... closer to 1 than it is to 100."

In 1986, the U.S. had 23317 nuclear warheads and Russia had 40519 for a total of 63836 weapons.

Chapter 11

A Tale of Two Speeches

page 169 - 173

In adding, as he [Gilpatric] did, nearly all my points, he totally changed the tone and bearing of his draft. Some of my language didn't get in, but this did:

Our confidence in our ability to deter Communist action, or resist Communist blackmail, is based upon a sober appreciation of the relative military power of the two sides. We doubt that the Soviet leadership has, in fact, any less realistic views, although this may not always be apparent from their extravagant claims. While the Soviets use rigid security as a military weapon, their Iron Curtain is not so impenetrable as to force us to accept at face value the Kremlin's boasts.

The fact is that this nation has a nuclear retaliatory force of such lethal power that an enemy move which brought it into play would be an act of self-destruction on his part.

That was the key point. My intended message was, for informed ears in the Kremlin and NATO, "We've discovered they are bluffing!" And for the American and European public: "We're staying in Berlin. and there's going to be no war." I thought of it as calling Khrushchev's bluff. I even rammed it home.

And with my new confidenvce that the U.S. patrols along the Berlin corridors would not be obstructed, I felt free to underline one committment in the final paragraph.

The United States does not seek to resolve disputes by violence. But if forceful interference with our rights and obligations should lead to violent conflict -as it well might [though i no longer believed this]- the United States does not intend to be defeated.

[Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell] Gilpatric gave the speech (in cache) [before the Business Council in The Homestead, Hot Springs, VA] on October 21, 1961, including these passages and others written by me, which were then quoted by the New York Times report of the speech.

Chapter 15

Burning Cities

page 262 - 263

LeMay himself was convinced that fire bombing had brought the Japanese to the point of surrender and that the atom bomb was in no way necessary. That last opinion was not at all confined to Air Force commanders, though Navy commanders, with reason, put more emphasis on the effects of the submarine blockade. The judgement that the bomb had not been necessary to victory -without invasion- was later expressed by

(Eisenhower and Halsey also shared Leahy's view that its use was morally reprehensible.) In other words, 7 of the 8 officers of 5-star rank in the U.S. Armed Forces in 1945 believed the bomb was not necessary to avert invasion (that is, all but General Marshall, chief of staff of the Army, who alone still believed in July that invasion might have been necessary). Likewise, the U.S. Strategic Bombng Survey for the Pacific War concluded in July 1946 (in a report primarily drafted by Paul Nitze):

"Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts and supported by testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945 and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bomb had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated."

Whether that was true or not, the U.S. Army Air Force came out of the war convinced it had won the war in the Pacific by burning masses of civilians to death. Certainly that was the conclusion of Curtis LeMay. In contrast, his civilian superiors, Truman and Stimson, denied to the end of their lives that the commanders and forces under their authority had ever violated the code of jus in bello by deliberately targeting noncombatants. In LeMay's eyes, that was something of a semantic question. In a lengthy interview with historian Michael Sherry, he said, "There are no innocent civilians. It is their government and you are fighting a people, you are not rrying to fight an armed force anymore. So it doesn't bother me so much to be killing the innocent bystanders."

Chapter 16

Killing a Nation

page 273

This little-known story [of potential atmospheric ignition, chapter 17] reveals something about actual decision-making under uncertainty at high levels, especially under cover of secrecy, that we humans are understandably resistant to recogizing in our leaders. It reveals the original readiness to gamble with nuclear disaster - a willingness to undertake small and sometimes not-so-small risks of ultimate catastrophy - that leading officials in nuclear superpowers have been exhibiting ever since. It is not good news.

Chapter 19

The Strangelove Paradox

pages 305 - 307

The bottom line is that arrangements made in Russia and the United States have long made it highly likely, if not virtually certain, that a single Hiroshima-type fission weapon exploding on either Washington or Moscow -whether deliberate or the result of a mistaken attack (as in Fail Safe or Dr. Strangelove) or as a result of an independent terrorist action- would lead to the end of human civilization (and most species). That has been, and remains, the inevitable result of maintaining forces on both sides that are capable of causing nuclear winter, and at the same time are poised to attack each other's capital and control system, in response to fallible warnings, in the delusion that such an attack will limit damage to the homeland, compared with the consequences of waiting for actual explosions to occur on more than one target.

Here, then, is the actual situation that has prevailed for more than half a century. Each side prepares and actually intends to attack the other's "military nervous system", command and control, especially its head and brain, the national command headquarters, in the first wave of a general war, however it originates. This has become the only hope of preempting and paralyzing the other's retaliatory capability in such a way as to avoid total devastation; it is what must above all be deterred by the opponent. But in fact it, too, is thoroughly suicidal unless the other side has failed to delegate authority well below the highest levels. Because each side does in fact delegate, hopes for decapitation are totally unfounded. But for the duration of the Cold War, for fear of frightening their own publics, their allies, and the world, neither side discouraged these hopes in the other by ackowledging its own delegation.

The only change in this situation has been that in the first weeks of the Trump administration, Russian news reports have begun ackowledging that the Perimeter system persists. In a February 2, 2017, article, Pravda revealed that the commander of Strategic Missile Forces Lietenant-General Sergey Karakayev said five years ago in an interview in a Russian publication, "Yes, the 'Perimeter' system exists. The system is on alert. If there's a need for a retaliatory strike, the command for an attack may come from the system, not people". The Pravda report explained, "Nuclear-capable missile will thus be launched from silos, mobile launchers, strategic aircraft, submarines to strike pre-entered targets, unless there is no (sic) signal from the command center to cancel the attack. In general, ... one thing is known for sure: The doomsday machine is not a myth at all - it does exist".

Ten days after President Trump's inauguration in 2017, Pravda quoted his statements that "the United States should strengthen and expand the nation's nuclear capacity" and "Let it be an arms race", and then reported that "Not so long ago, the Russian Federation conducted exercises to repel a nuclear attack on Moscow and strike a retaliatory thermonuclear attack on the enemy. In the course of the operations, Russia tested the Perimeter System, known as the 'doomsday weapon' or the 'dead hand'. The system assesses the situation in the country and gives a command to strike a retaliatory blow on the enemy automatically. Thus, the enemy will not be able to attack Russia and stay alive".

[note added by J. Gruber:

W. Putin, Waldai-Forum, Sotschi, 18. Oktober 2018

"Ich erinnere Sie daran, worum es ging. Es ging darum, ob wir bereit sind und ich bereit bin, die uns zur Verfgung sthenden Waffen einschlie§lich der Massenvernichtungswaffen zu benutzen, um uns und unsere Interessen zu schtzen, und ich habe damit geantwortet "Ich erinnere Sie daran, was ich gesagt habe. Ich habe gesagt, dass in unserem Konzept des Einsatzes von Atomwaffen kein Prventivschlag stattfindet, und ich bitte alle hier und alle, die dann jedes Wort, das ich sage, analysieren und in eigenen Aussagen verwenden, folgendes im Hinterkopf zu behalten.

- Wir haben keinen Prventivschlag in unserem Konzept des Einsatzes von Atomwaffen. Unser Konzept ist ein Vergeltungsschlag. Fr diejenigen, die das wissen, ist es nicht notwendig zu erlutern, was das bedeutet.

- Wir sind bereit und wir werden nur dann Atomwaffen verwenden, wenn der Aggressor in Russland zuschlgt, auf unserem Territorium.

- Wir haben ein System geschaffen und verbessern es stndig -es muss verbessert werden- GWS, ein Raketen-Frhwarnsystem.

- Dieses System erfasst auf globaler Ebene, welche Arten von Starts von strategischen Raketen aus den Meeren und Lndern durchgefhrt werden. Das ist das erste.

- Und zweitens bestimmt es den Flugweg.

- Als drittes bestimmt es die Region, in dem die Atomwaffen znden werden.

- Wenn wir berzeugt sind, das geschieht innerhalb von ein paar Sekunden, dass der Angriff auf das Territorium von Russland zielt, nur dann schlagen wir zurck auf gegenseitiger Basis.

Warum "gegen"? Weil der Aggressor auf uns zurck fliegt (sic) [vielleicht besser: Weil die Aggression auf ihn, den Aggressor, zurckschlgt.]. Natrlich ist dies eine globale Katastrophe, aber -ich wiederhole- wir knnen nicht die Initiatoren dieser Katastrophe sein ohne Prventivschlag. Nein, in dieser Situation warten wir auf den Einsatz von Nuklearwaffen gegen uns und tun selbst aber nichts. Aber dann muss der Aggressor wissen, dass Vergeltung unvermeidlich ist und er zerstrt wird.

Wir werden das Opfer der Aggression und wrden als mrtyrer in den Himmel kommen, und sie wrden einfach sterben ohne die Zeit, wenigstens Bu§e zu tun.

(Die Rede wurde bersetzt nach dem Originalmanuskript des Kreml.]

What has not changed is American preoccupation with threatening Russian command and control: as if all the above revelations, including those of Blair and Yarynich, had not occurred or were thoroughly disbelieved. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, passed with bipartisan support and signed by President Obama on December 23, 2016, included a provision which mandated a report by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Strategic command on "Russian and Chinese Political and Military Leadership Survivability, Command and Control, and Continuity of Governmental Programs and Activities". The provision of the law for the U.S. Strategic Command to "submit to the appropriate congressional committees the views of the Commander on the report ... including a detailed description of how the command, control, and communication systems" for the leadership of Russia and China, respectively, are factored into the U.S. nuclear war plan. The Pravda news stories quoted above, both apperaing in the second week of the Trump administration, were explicitly responding to these provisions of this law signed a few weeks earlier in their explanation of the continuing need for Perimeter.

Such plans and capabilities for decapitation encourage -almost compel- not only the Perimeter system but Russian launch on (possibly false) warning: either by high command (in expectation of being hit themselves imminently, and in hopes of decapitating the enemy commanders before they have launched all their weapons) or by subordinates who are out of communication with high command and have been delegated launch authority.

As General Holloway expressed it in 1980, he had confidence that with such a decapitating strategy, a U.S first strike would come out much better for the United States than a second strike, to the point of surviving and even prevailing. He was right about the hopelessness of the alternative forms of preemption. But in reality, the hope of successfully avoiding mutual annihilation by a decapitating attack has always been as ill-founded as any other. The realistic conclusion would be that a nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviets was -and is- virtually certain to be an unmitigated catastrophe, not only for the two parties but for the world. But being unwilling to change the whole framework of our foreign and defense policy by abandoning reliance on the threat of nuclear first use or escalation, policy makers (probably on both sides) have chosen to act as if they believed (and perhaps do believe) that such a threat is not what it is: a readiness to trigger global omnicide.

page 318

"It has never been true that nuclear war is 'unthinkable', wrote British historian E.P. Thompson. "It has been thought and the thought has been put into effect." He was referring to President Harry Truman's use of atomic bombs to destroy the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. What needs further attention is that the president who ordered these attacks -along with the great majority of the American public- regarded these nuclear attacks as marvelously successful. Such thoughts get thought again, and acted on.

Among military planners in the U.S. government, thinking about nuclear war has in fact been continuous over the last seventy-two years and not only, or even mainly, with respect to deterring or responding to a Soviet nuclear attack on the United States or its forces or allies. Preparations and committments to initiate nuclear war "if necessary" have been the basis of fundamental, langstanding U.S. policies and crisis declarations and actions not only in Europe but in Asia and the Middle East as well.

page 319

The notion common to nearly all Americans that "no nuclear weapons have been used since Nagasaki" is mistaken. It is not the case that U.S. nuclear weapons have simply piled up over the years, unused and unusable, save for the single function of deterring their use against us by the Soviets. Again and again, generally in secret from the American public, U.S. nuclear weapons have been used, for quite different purposes.

As I noted earlier, they have been used in the precise way that a gun is used when you point it at someone's head in a direct confrontation, whether or not the rtigger is pulled. For a certain type of gun owner, getting their way in such situations without having to pull the trigger is the best use of the gun. It is why they have it, why they keep it loaded and ready to hand. All American presidents since Franklin Roosevelt have acted on that motive, at times, for owning nuclear weapons: the incentive to be able to threaten to initiate nuclear attacks if certain demands are not met.